LONDON, United Kingdom – Zimbabwe’s Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) likely has a secret stream of money, The Sentry has found. Publicly available information suggests that the CIO controls Terrestrial Holdings, a business conglomerate of companies involved in hemp, solar energy, coal mining, tourism, and golf.

The CIO’s remit includes both domestic and international intelligence matters, and its agents have been accused of partisan and violent behaviour in the past. For instance, in the 2023 election, one of the agency’s leaders helped establish a ruling party affiliate criticised for intimidating rural voters.

While the bulk of the CIO’s funds come from the official budget, the agency—which has a dedicated investment branch—has been known to engage in private business ventures as a source of off-budget financing. In the past, CIO joint ventures have been involved in mushroom farming, exporting baby elephants, and diamond mining. Most recently, CIO-linked companies Terrestrial Mining and Whitelime Mining have been awarded coal mining concessions covering 50,000 hectares near Lake Kariba in western Zimbabwe, an area close to large proposed and existing coal-fired power plants.

Terrestrial Holdings and Terrestrial Mining said that claims of CIO control or ownership were not true.

The existence of an autonomous CIO business network matters because the agency—which has reportedly engaged in election-related intimidation—requires civilian control, including full financial oversight and transparency, to prevent abuse. Security forces with their own sources of revenue can more easily go rogue.

The Sentry was able to conclude that the CIO likely controls Terrestrial Holdings by following clues about a past network of CIO companies, which made it possible to draw up a list of company directors and identify an address, both linked to the spy agency.

A parliamentary hearing leads to a list of CIO-linked directors

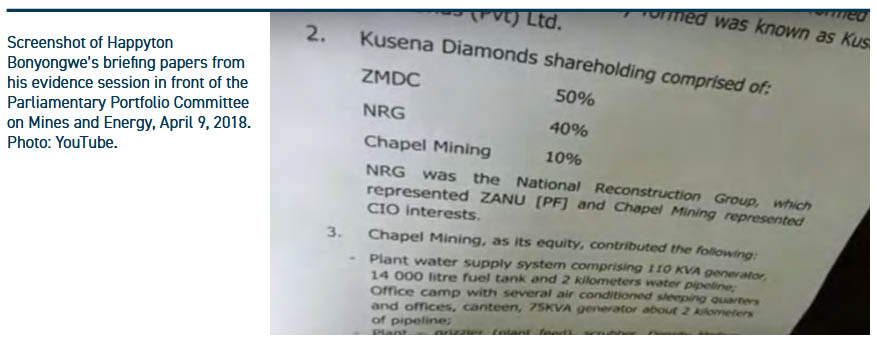

In 2018, former CIO Director General Happyton Bonyongwe sat in a crowded committee room in the old parliament building, answering questions about revenue from CIO-owned Kusena Diamonds—a hot topic, as former President Robert Mugabe had alleged that billions of dollars of diamond money had gone missing.

Formed in 2012, Kusena was not the first diamond mining company that the President’s Department—the official name for the spy agency—had been linked to. During the 2009-2013 coalition period, when the opposition controlled the Treasury, the CIO had set up diamond mines in order to “raise funding to supplement the meagre resources which were coming out of the Ministry of Finance,” Bonyongwe told the committee.

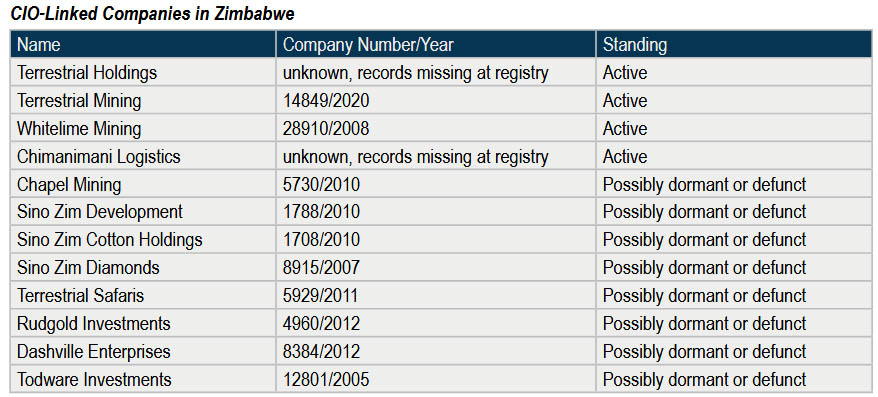

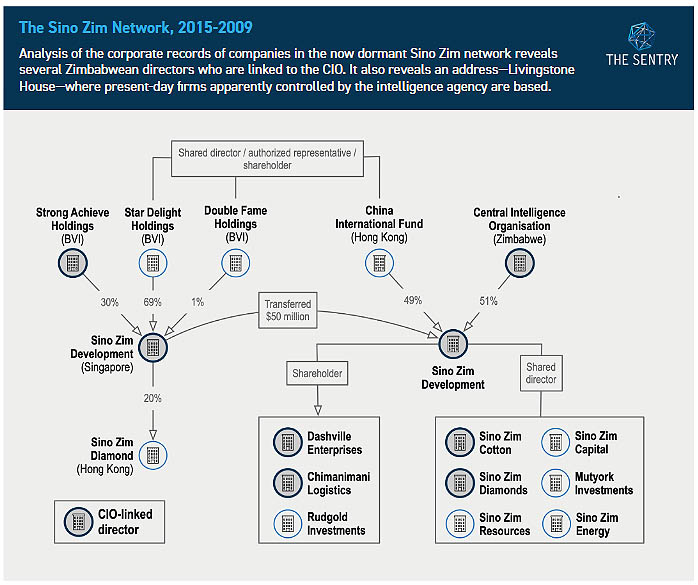

Between 2007 and 2012, the CIO established Sino Zim Diamonds as well as a series of similarly named ventures—Sino Zim Cotton, Sino Zim Resources, Sino Zim Development—with a Chinese-Angolan entrepreneur known as Sam Pa. These companies—together with associated firms like Mutyork Investments and subsidiaries such as Dashville Enterprises, Rudgold Investments, and Chimanimani Logistics—had interests in property, tobacco, and cotton.

The Sino Zim network also contained similarly named sister companies in Asia: Sino Zim Development Pte in Singapore provided at least $50 million in funding to its eponymous counterpart in Zimbabwe, and it also part-owned Sino Zim Diamond, registered in Hong Kong.

Later, after Pa withdrew from Zimbabwe, the Sino Zim diamond concessions—blocks H and D in Marange, in eastern Zimbabwe—were taken over by Kusena in 2011-2012.

Bonyongwe was at pains to stress to the committee that Kusena never made any money for the agency. However, while it was active, the earlier Sino Zim network had been a valuable asset for the CIO. Firms linked to Sam Pa provided at least $1 million and 100 pickup trucks to the CIO in the run-up to the 2013 elections, while Sam Pa himself was involved in diamond deals.

In 2014, Sam Pa and several Sino Zim companies—Sino Zim Development, Sino Zimbabwe Cotton Holdings, and Sino Zimbabwe Holdings—were sanctioned by the United States for undermining democracy through their off-budget financing of the CIO. Sam Pa was later detained and has been held incommunicado in China since 2015, reportedly as part of a corruption investigation. His network of companies languished, with some limping on and others—including the Zimbabwean firms—seemingly defunct.

Representatives of the Sino Zim companies and other companies in their group, such as Mutyork Investments, Star Delight Holdings, and Double Fame Holdings, failed to respond to requests for comment, while attempts to contact Kusena were unsuccessful.

During the hearing on Kusena, Bonyongwe gave valuable clues—both deliberately and accidentally—about how the CIO structured its investments. He described how Kusena’s board, chaired by businessman Jonathan Kadzura, had members “representing the [President’s] Department” and how the board then reported upward to the CIO’s investment committee, headed by the agency’s deputy director general.

These details were volunteered by Bonyongwe. However, by leaving his speaking notes on show for the cameras, Bonyongwe also inadvertently revealed the name of the holding company through which the agency owned 10 percent of Kusena.

According to Bonyongwe’s briefing papers, half of Kusena was owned by the state-owned Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC), while 40 percent was allocated to an entity called the National Reconstruction Group, a front for the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (Zanu PF) party. The remaining 10 percent was held by the CIO-owned Chapel Mining.

The corporate records for Chapel Mining and the Sino Zim companies provide a list of directors whose names help establish links between the CIO and firms still active today. Some of the directors were drawn from the CIO’s specialist branches for administration or economic analysis.

The office building housing Chapel Mining and Sino Zim companies leads to CIO-linked firms active today, including Terrestrial Holdings

The CIO’s partial ownership of Sino Zim Development, Kusena Diamonds, and Chapel Mining is beyond doubt: the CIO said as much, or, in the case of Chapel Mining, accidentally revealed their claim in the parliamentary hearings.

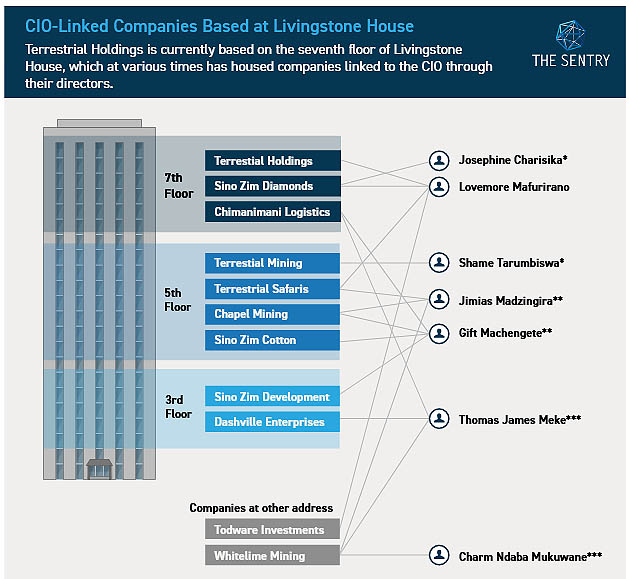

Corporate records for these companies list their registered offices—offices that were apparently shared with Terrestrial Holdings.

Chapel Mining and most of the Sino Zim companies operated from the third, fifth, and seventh floors of Livingstone House, a 1960s office block in central Harare. China Sonangol, a company closely linked to Sam Pa, claimed to own the building, according to an archived 2013 version of its website. One visitor to the fifth floor in the mid-2010s recalled meeting notorious CIO officers there, such as the late Joseph Mwale, accused of burning people alive in 2000.

The fifth floor once housed Terrestrial Safaris, another CIO-linked entity with Jimias Madzingira, Gift Kallisto Machengete, and Lovemore Mafurirano as directors. The firm—now seemingly dormant—controlled hunting rights leased from Zimbabwe’s Parks and Wildlife Authority and was reported to have been involved in the export of baby elephants to Chinese zoos in 2015. Also based on the fifth floor of Livingstone House is Terrestrial Mining, which—alongside CIO-linked Whitelime Mining—has recently been awarded coal mining concessions in western Zimbabwe.

Terrestrial Holdings has payment devices on the fifth floor of Livingstone House, according to a list of point of sale (POS) terminals published by CBZ Bank. Terrestrial Holdings also has POS terminals in Harare Golf Club South and on the seventh floor of Chester House—another Harare office block. Masimba Ignatius Kamba, former acting director of economics for the CIO, gave the same floor of Chester House as an address when he signed the corporate documents for the Singaporean company Sino Zim Development.

In 2013, a journalist visited both Livingstone House and Chester House in an attempt to track down Kamba. At Chester House, where the Zimbabwean Congress of Trade Unions was then based on the ninth and tenth floors, a trade unionist told the reporter, “The sixth and seventh floors, that’s where we have the CIO guys. We don’t relocate because they just follow us.”

The “mushroom king” suggests Lovemore Mafurirano headed Terrestrial Holdings Terrestrial Holdings was first linked to the CIO by the Zimbabwe Independent newspaper in 1999, when the paper identified the firm as the owner of several of the agency’s safe houses. Property deeds confirm that Terrestrial Holdings bought at least seven properties, some in affluent Harare neighborhoods such as Borrowdale Brook and Glen Lorne.

Terrestrial Holdings’ interests in real estate were corroborated by an insider, who said the firm had four departments: “property, hospitality, farming, [and] solar energy.” It ran Harare South Golf Club as a wedding venue and owned a farm near Mazowe, just north of the capital. Terrestrial Holdings’ subsidiaries also included a solar company called Todware Investments, according to the source.

Social media posts from Terrestrial Holdings confirm that the firm has participated in a wide range of sectors. Jobs at Terrestrial Holdings have included safari operator, energy engineer, accountant, project manager, agronomist and farm manager, and property manager. Other posts suggest that Terrestrial Holdings has also moved into the marijuana industry, growing hemp and cannabis for cannabidiol (CBD) near Mazowe, north of Harare, at New Valley Farm—a farm reportedly seized by the CIO during the fast-track land reform process in the 2000s. Some staff seemed to transition from the Sino Zim network to Terrestrial Holdings as well, according to LinkedIn profiles. For example, Nicholas Rgwambiwa was a director of Rudgold Investments, a subsidiary of Sino Zim Development, and later worked for Terrestrial Holdings. Attempts to reach Rgwambiwa for comment were unsuccessful.

Terrestrial Holdings’ managing director, meanwhile, was Lovemore Mafurirano, an insider told The Sentry. Ding Lunbao, a Chinese entrepreneur known as “the mushroom king,” provides confirmation: According to his company’s website, in 2017 the businessman met Mafurirano, who was “in charge of” Terrestrial Holdings, to discuss mushroom farming. The mushroom king’s website also described Mafurirano as the deputy director of the investment branch of the President’s Department. Apps that reveal the name under which a phone number is stored show Mafurirano’s number listed under “Mafurirano AsDir,” a likely reference to “assistant director.” A recent obituary in state-controlled media for Nyasha Dzimiri, who was the “Director Investments” in the President’s Department, included praise from a “Lovemore Mafuriranwa,” described as the “Deputy Director Investments in the President’s Department.” In addition, there is an “L Mafurirano” named in a 2012 court case as chairman of a disciplinary board of enquiry into the behaviour of a district intelligence officer (DIO) at the CIO.

When asked if he was still at the President’s Department, Mafurirano said, “I am no longer there. And you cannot just phone me.” Lunbao could not be reached for comment.

Mafurirano was also reportedly the executive director of Todware, according to media coverage of a separate 2013 court hearing. The company secretary for Todware, Farai Machekanyanga, registered his address as the seventh floor of Chester House, and someone with the same name is listed as a DIO in the leaked 2001 CIO phonebook. Machekanyanga could not be reached for comment.

Other publicly available clues also point toward a link between the CIO and Terrestrial Holdings. Phone numbers used by Terrestrial Holdings and Todware staff show up in contact apps listed as “President Office Deeds,” “CIO Ndambambi,” “CIO Museka Farmer,” “Mashingaidze CIO,” and “DIO Admin GPSI.” In old online business directories, Terrestrial Holdings’ previous office was listed at 4 Crighton Road, Groombridge, Harare, an address that later was reportedly named in 2022 court proceedings in which dismissed CIO administrative staff alleged mismanagement in the agency’s renovation of that property.

Terrestrial Holdings goes public

A website for Terrestrial Holdings appeared in November 2023. The Zimbabwe Independent reported that the company—described by the newspaper as “a firm with suspected links to the CIO”—had obtained a license for exporting raw lithium.

The website confirms several details gleaned from the online clues: It listed Terrestrial Holdings’ address as the seventh floor of Livingstone House and stated that the firm had an interest in coal mining near Lake Kariba in western Zimbabwe. The site describes Terrestrial Holdings as a business conglomerate with interests in mining gold, coal, and lithium; farming hemp; real estate; telecommunication; solar and thermal energy; transport and logistics; and game range drive services for tourists.

When approached, Terrestrial Holdings denied being a CIO front company. However, given that it shared a property address with known CIO companies like Chapel Mining; that its first listed address in Harare was identified as a CIO building in a court case; that its managing director in 2017, Mafurirano, was previously a co-director in Sino Zim Diamonds and Terrestrial Safaris alongside other senior CIO staff members; and that Terrestrial Holdings’ staff are listed as CIO members in various phone contact apps, it seems likely that the firm is controlled by the agency.

Conclusion

The CIO’s secret business interests might matter less if the organisation was a politically neutral and accountable intelligence agency, gathering information and defending against threats to Zimbabwe’s democratic constitution. This is far from the case. During the 2023 elections, the CIO reportedly intimidated opposition candidates, and its deputy director general helped establish Forever Associates Zimbabwe, a Zanu PF affiliate criticised for intimidating rural voters—an allegation that both the spy boss and FAZ deny.

Several victims of political violence and threats identified CIO agents as the perpetrators, according to a joint report by Zimbabwean human rights watchdogs and police complaints reviewed by The Sentry.

National security organs require comprehensive oversight mechanisms to prevent abuse. International best practices compiled by the United Nations Human Rights Council state that “an effective system of intelligence oversight includes at least one civilian institution that is independent of both the intelligence services and the executive.” This oversight role should include “examining whether intelligence services make efficient and effective use of the public funds allocated to them.”

Civilian control of the security forces requires full financial control. Militaries and intelligence agencies with access to independent off-budget sources of income are more capable of setting their own agendas—without seeking funding or approval from elected civilian politicians.

Recommendations

The government of Zimbabwe

The government of Zimbabwe should dissolve the CIO’s businesses, wind up its investment branch, and ensure through appropriate national security legislation that there is, in future, just one source of revenue for the agency, voted for by Parliament in the annual budgeting process. This would enable better oversight and accountability and allow for security priorities to be balanced against other civilian funding requirements during the budgeting process.

The government should introduce an online, public corporate registry of directors and beneficial owners to replace Zimbabwe’s difficult-to-access paper-based system in which up-to-date information is often missing. At present, the records for Terrestrial Holdings and Chimanimani Logistics are missing from the company registry, while the records for Whitelime Mining appear to be out of date.

Banks and commercial counterparties

Banks and firms doing business with Terrestrial Holdings and related companies should conduct enhanced due diligence—consistent with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights—into the ownership structure of the entity to identify and mitigate risks associated with direct or indirect support for a state security agency whose members are accused of human rights abuses and undermining democracy.

Companies operating in Zimbabwe’s coal mining sector should conduct ongoing due diligence consistent with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals From Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, with particular attention paid to identifying and mitigating risks associated with direct or indirect support for the state security agency, whose members are accused of human rights abuses and undermining democracy.