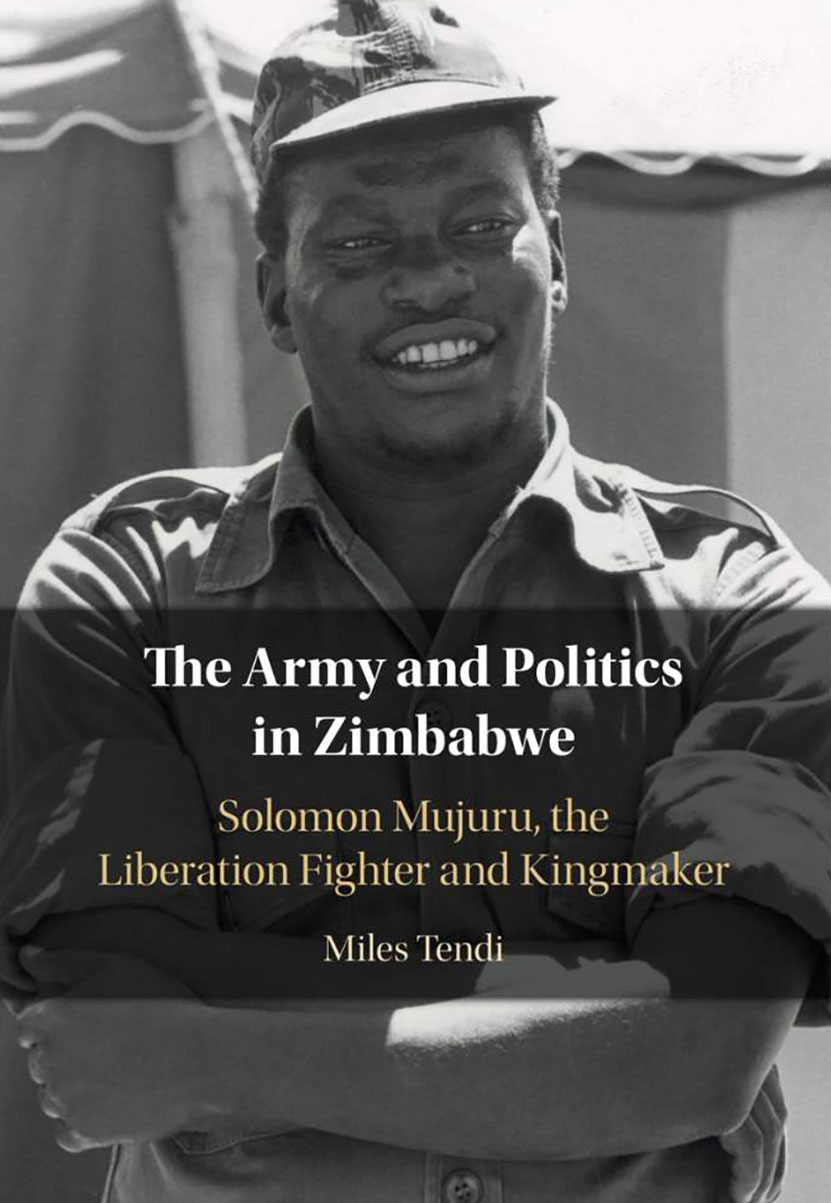

LONDON, United Kingdom – A newly published scholarly biography of the late retired commander of the Zimbabwe National Army, General Solomon Mujuru, captures the liberation war hero’s key role in shaping the history of Zimbabwe and challenges the official narrative on his death, allegedly in a house fire in 2011.

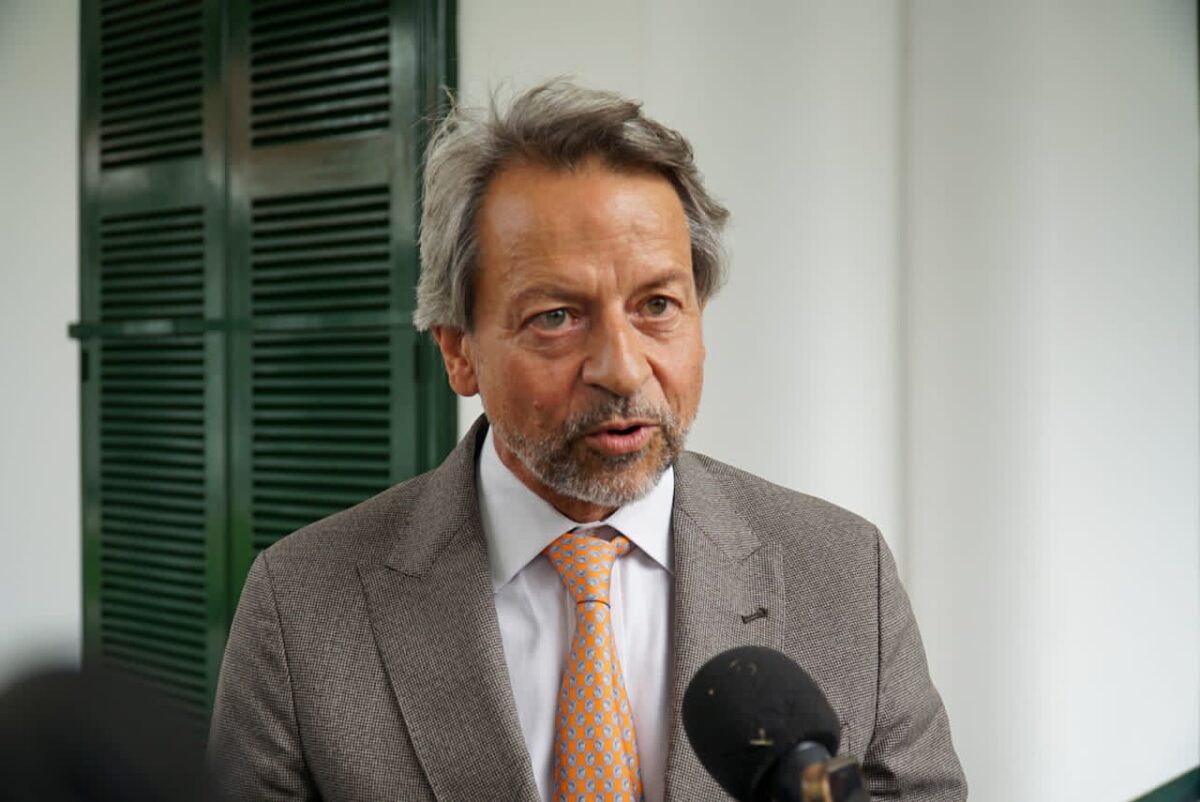

Blessing Miles Tendi, a professor of African politics at the University of Oxford, launched his 10-year effort of meticulous research into Mujuru’s life and death at The School of Oriental and African Studies in London on 17 February 2020.

Titled “The Army and Politics in Zimbabwe: Mujuru, the Liberation Fighter and Kingmaker”, the book centres on the life of the man who was also known by his war-time nom-de-guerre, Rex Nhongo, and traces his strategic role in Zimbabwe’s recent military and political histories, as well as in the transnational politics of Southern Africa’s 1970s liberation struggles.

Explaining the book’s contribution to the country’s liberation and post-independence historiography, Tendi said: “Many facets of the politics of the Zimbabwean army, and (the ruling party) ZANU PF’s liberation struggle and independence time elite politics, have remained obscure in the academic literature. My book sheds important light on critical themes such as internal succession politics, the nature of host-hostee relations in wars of liberation and contested post-conflict military integration.

“I wanted to publish a panoramic take on the liberation war and independence politics. Rex’s life history combines these two historical phases, so he is the ideal prism through which to view both periods. He embodies important turning points in the military and political histories of his time, making him an ideal prism.”

The first historical turning point that Mujuru was involved in came in 1971 when, as part of the better trained and conventional soldiers of ZIPRA, ZAPU’s military wing, he defected to ZANLA, Zanu-PF’s guerrilla army. The defectors included Mujuru, Thomas Nhari, Dakarai Badza, David Todhlana, and Robson Manyika, among others.

These former ZIPRA fighters greatly enhanced ZANLA’s operational capabilities, and they were also key actors in the 1974 Nhari revolt, which was primarily led by field commanders Thomas Nhari, Dakarai Badza and Caesar Molife. Tendi contends that the mutineers took advantage of the absence of the ZANU and ZANLA leaderships, which were abroad on various transnational diplomatic engagements in countries sympathetic to Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle, to stage a revolt.

The mutiny could have been avoided had the ZANLA commander, Josiah Tongogara, heeded Mujuru’s advice that ZANU’s transnational appointments be postponed in order first to address growing dissent among guerrillas at the war front.

The second turning point followed the March 1975 assassination in Zambia of ZANU’s chairman, Herbert Chitepo. Mujuru became the most senior commander outside prison after Tongogara and others were rounded up and arrested by the Zambian authorities, who believed Chitepo had been killed by his colleagues in ZANU.

Thirdly, Mujuru was to star in the formation of the Zimbabwe People’s Army (ZIPA), which brought together ZANLA and ZIPRA forces in a short-lived united fighting force.

Then in 1977, Mujuru was to play perhaps one of his most critical roles in the evolution of Zimbabwean history when he persuaded reluctant military colleagues to accept the leadership of Robert Mugabe. This paved the way for what would become four decades of Mugabe’s dominance over both Zanu-PF and independent Zimbabwe.

The final turning point came after his retirement from the military in 1992, when Mujuru was co-opted into the Zanu-PF Politburo, the ruling party’s elite decision-making body. As told to Tendi by the late liberation icon and former home affairs minister, Dumiso Dabengwa, Mujuru wasted no time in instigating leadership renewal and succession politics in the ruling party.

Dabengwa, a close ally of Mujuru’s, told the story of one Politburo meeting where Rex, as he called Mujuru, raised his arm, with bloodshot eyes firmly fixed on Mugabe, to make a statement in his customary stuttering voice.

“I want to say you, the President, and Vice President (Joshua) Nkomo, should consider retiring. Give others a chance,” Mujuru said. Mugabe kept quiet. Nkomo took his stick, angry, jumped up and said, ‘Wena mfana, thula!’ [You, boy, shut up!] Everybody started laughing and then Rex said: “M-m-m-m-m-mandinzwa’ [You have heard me!]”

It is such clashes with his fellow Zanu-PF and establishment elites over leadership renewal at the helm of both party and state that came to dominate Mujuru’s politics, right up to his untimely and highly suspicious death, allegedly in a house fire at his Beatrice farm in August 2011.

In the last chapter of the book, Tendi devotes considerable effort in debunking the official verdict of the cause and circumstances of Mujuru’s death, with the aid of some compelling evidence provided by a variety of sources, including Mujuru’s family. He also exposes the series of deliberate actions by the state and investigating authorities to frustrate any thoroughgoing inquiry into Mujuru’s death. Bizarrely, the state concluded, without any DNA testing of the charred remains found in Mujuru’s farm house, that the remains were the retired general’s, and proceeded to have him buried.

Tendi’s book has been hailed by his academic peers as arguably the most evidenced work of political history on Zimbabwe to be published to date.

Published by Cambridge University Press, the book is available in hardback on Amazon, and a more affordable paperback option is available on the publishers’ African branch website