HARARE – President Emmerson Mnangagwa said on Tuesday that a decision to ban the use of foreign currencies was an important step to repair the economy, but local businesspeople and investors were wary a day after the reform was announced.

Mnangagwa is trying to attract investment and lift growth after a litany of failed economic interventions under his predecessor, Robert Mugabe.

His government said on Monday the country’s interim RTGS dollar would be the only legal tender, ending a decade during which multiple currencies including the U.S. dollar had been accepted in shops.

But the surprise manner in which the latest currency reform was announced, and Zimbabwe’s track record of printing money to plug holes in its public finances, mean many people do not believe it will succeed.

With inflation close to 100 percent last month and desperate levels of unemployment, Zimbabweans are impatient for progress. Unions are threatening strikes if the government does not overturn its policy.

“It has always been clear that for our economy to truly take off, we need our own currency,” Mnangagwa said in a statement.

“While the multi-currency regime helped stabilise the economy, it did not give us control of monetary policy and left us at the mercy of U.S. dollar pricing which has been a root cause of inflation.”

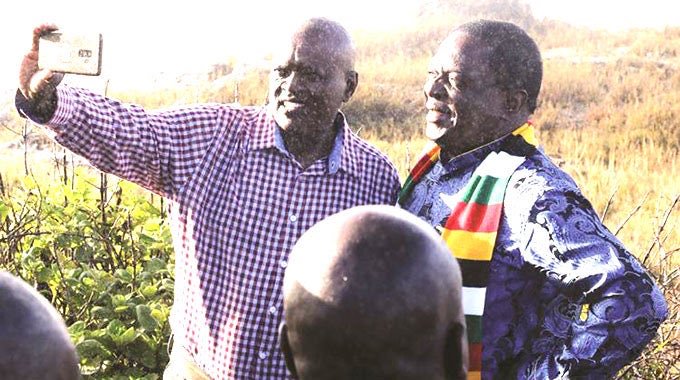

In remarks to journalists in Victoria Falls, Mnangagwa said: “Zimbabwe has gone back to normalcy, and the normalcy is a country must be having its own currency. We were living in an abnormal situation, and you should be the first to congratulate us for being normal again.”

In the capital Harare, major grocery and fast food chains appeared to heed the directive to stop accepting foreign currencies, but some informal traders selling clothes, car parts and electronics vowed to defy the new rules.

“If I stop taking U.S. dollars, how am I going to replace my stock? I have not seen anyone who got U.S. dollars from the bank in a long time,” said a clothes seller who only wished to give his first name, Thomas.

In the second city, Bulawayo, a bar owner declared: “I will continue accepting U.S. dollars until they arrest me. I order most of my stock in South Africa and for that, I need real money. The RTGS is not money.”

The RTGS firmed slightly on the black market on Tuesday, but exchange rates were quoted in a wide range, between 7 and 11 to the U.S. dollar compared with between 11 and 12 on Monday, reflecting uncertainty about how the reform would pan out.

Traders attributed the generally firmer rate to tight availability of the RTGS a day after the central bank hiked its overnight lending rate to 50 percent from 15 percent and announced plans to try to curtail RTGS liquidity.

Zimbabwe introduced the RTGS as a transitional unit in February as a step towards relaunching the Zimbabwean dollar.

The Zimbabwe Stock Exchange’s industrial index fell 0.7 percent on Tuesday, breaking a sustained rally. Volumes were thinner, with shares worth 4.3 million RTGS traded on Tuesday, down from 32 million RTGS on Monday.

One sign Zimbabweans are distrustful of the RTGS is that it is weaker on the black market than on the official interbank market, where it trades around 6 to the dollar.

Analysts are sceptical that Zimbabweans and local firms will sell foreign currency to buy RTGS, as the government wants them to, unless they are forced.

They point out that Zimbabwe has few foreign-currency reserves with which to defend the RTGS.

The Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU), the country’s largest labour body, and the main opposition MDC sharply criticised the decision to switch to using the RTGS as the country’s sole currency.

“If the government does not reverse this ruinous policy immediately and announce U.S. dollar salary payments, we will immediately mobilise workers for mass action,” ZCTU president Peter Mutasa told reporters.

The ZCTU – which groups teachers, factory workers, mine workers, farmhands and others – led protests against a 150 percent fuel price increase in January, triggering a violent crackdown by the army and police that left at least 18 people dead, according to rights groups.

The MDC’s head of policy and research, Tapiwa Mashakada, said the currency reform would exacerbate widespread shortages of critical goods.

“The wheels have finally come off as the Zimbabwe government has been cornered and forced to involuntarily de-dollarise without a plan,” Mashakada said. “At present Zimbabwe cannot afford a paper currency which has no economic value.”

Former finance minister and the MDC’s vice president Tendai Biti said on Twitter: “Years after Emmerson and his lot are gone, Statutory Instrument 142 of 2019 will be remembered as the turning point. Their Sarajevo. That moment it became clear even to the most ardent that they had outlived their usefulness. That they had become a threat not only to the country but to themselves too.”

“A currency is a mirror of the national economy. It reflects output. It reflects the current account. It reflects confidence and fundamentals. It is absolutely insane to de-dollarise without production, without reserves and with a confidence deficit. It is politics.”