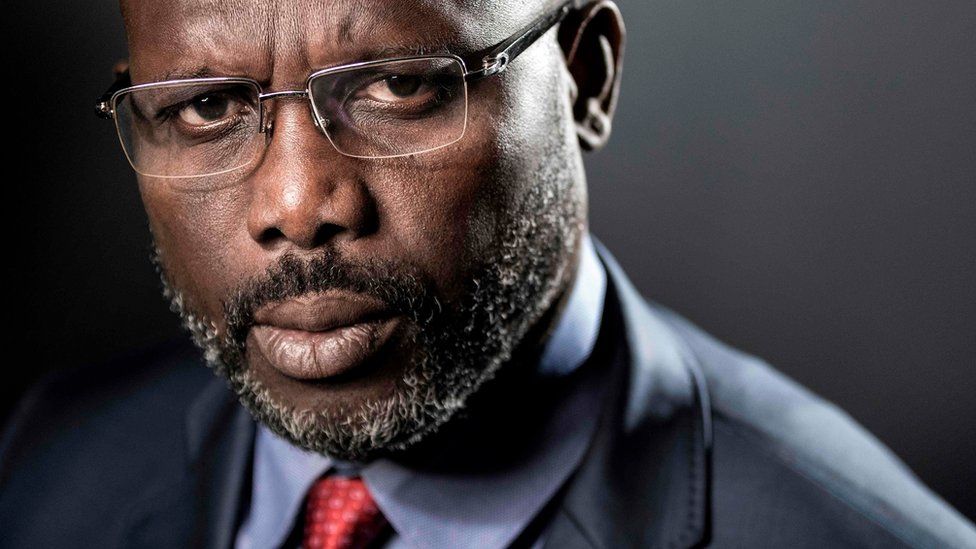

LIBERIA, Monrovia – Former football star George Weah is running for a second six-year term as Liberia’s president, but he appears to have scored an own goal by failing to engage with the topic that is dominating the air waves and mood on the streets – demands to set up an economic and war crimes court.

The 57-year-old came into power promising to create jobs, transform lives and set up the court.

But after taking office in 2018 he argued that looking backwards at old crimes would not be the best way to achieve development – something 24-year-old Frederick Tulay feels is a mistake.

“As a first-time voter in 2017, I believed President Weah. But he has refused to address corruption in the public sector. Many of the youth are using drugs because they are jobless,” he told the BBC, saying he would not be voting this time for Mr Weah and his Congress for Democratic Change party.

Tulay lost his job in a factory for a construction firm two years ago when his former employer could no longer pay his salary. He now works as a taxi driver but business is not flourishing: “The roads are very bad and gas is expensive. My dream is to leave the country.”

His comments reflect a commonly felt anger – that 20 years after the end of the country’s brutal two civil wars, in which an estimated 250,000 died, most people are still struggling to survive.

The country operates a dual currency system, meaning those paid in Liberian dollars often need to pay for imported food or other items in US dollars – making life extremely expensive.

Two financial scandals over the last few years have also shocked Liberians, leading to the US imposing sanctions on several officials, including Mr Weah’s chief of staff.

For 49-year-old Peterson Sonyah, failing to address the wounds of the past has led to this culture of impunity.

The survivor of a horrific civil war massacre at a church in the capital, Monrovia, he now spends his time campaigning for the perpetrators of the civil wars, and those who profited financially from them, to be prosecuted.

As a 16-year-old he sought refuge in the church with his father, who was one of around 600 killed by soldiers in 1990.

“When the soldiers ran out of ammunition, some of them went to get more so people tried to escape but the soldiers started attacking them with machetes,” he remembers as he points at bullet holes on the windows at St Peter’s Lutheran Church.

The need for a court is urgent, he maintains: “Some people are already telling me that since there’s no justice, we should take up arms and start waging war against the people.

“They believe if we did that, in the future we would get lucrative jobs and live the best lives because they are seeing the example. We are all human beings, people can get tempted.”

Nineteen other candidates are challenging Mr Weah for the presidency next Tuesday, including former Vice-President Joseph Boakai, businessman Alexander Cummings and human rights lawyer Tiawan Gongloe.

These three contenders have pledged to set up the court if elected – though some have expressed doubts about Mr Boakai’s commitment, given his alliance with former warlord Prince Yormie Johnson, now a serving senator.

One of the most vocal calls for a court comes from Yekeh Kolubah, a former child soldier, recruited in the 1990s by Charles Taylor’s NPLF rebels, and an incumbent MP from Montserrado County.

He wants all suspected perpetrators to have their day in court – himself included.

“We want the economic war crimes court… because I want to go there and be able to exonerate myself. Let the people know the wrong I have done and let me be penalised for it.”

Very popular with young people, the child rebel-turned-politician walked briskly, like a soldier, to sit on a plastic chair in his press centre set up in a poor area of Monrovia for our interview.

Like Mr Sonyah, he believes the court would allow Liberia to move forward and heal: “If we don’t do this, that means we are still encouraging war. The reason we are behaving violently is because we have not been punished.

“If I go to jail for brutalising people, for killing people, do you think I will hold a gun again?”

He is angered by what he says are attempts to silence him on the subject with offers of lucrative parliamentary committee positions.

Information Minister Ledgerhood Rennie told the BBC the president would not comment on such allegations, dismissing Mr Kolubah as a “well-known lunatic rabble rouser”.

The deputy finance minister pointed out that the final decision on a war crimes court essentially lies with parliament.

“The people should tell their legislators to make the issue the most important during their campaign and stay committed to it,” Samora Wolokolie told the BBC.

Mr Rennie said it could even be a matter that has to go to a referendum.

But Liberian group Global Justice and Research Project (GJRP), which has been documenting evidence of war crimes, believes the government is not interested in facilitating either option.

Its director Hassan Bility said a letter signed by more than 50% of lawmakers, including Mr Kolubah, calling for the matter to be discussed in parliament was twice “lost” by speaker of the House of Representatives.

“The peace Liberia is enjoying, I don’t believe it’s durable or sustained peace because there are no deterrent mechanisms in place,” Mr Bility told the BBC.

The elections will be the first since the exit of UN peacekeepers who were deployed after the official end of the civil wars in 2003.

Mr Wolokolie says President Weah has to be given credit for steering the country through Covid-19 and creating jobs in the public sector.

His supporters also applaud him for the road building that has taken place across the country over the last six years – he once said he was the medicine needed to treat bad roads, earning himself the affectionate nickname “Bad Road Medicine”.

The former Fifa World Footballer of the Year can still attract huge crowds at his rallies. He has that star quality, and many fans in the capital.

Wleh Potee, a supporter of the president who sells wristwatches and sunglasses in the heart of Monrovia, notes that the economic crunch is not specific to Liberia. And while his own sales are significantly down, he says he and other traders are happy with the president.

“In the past, police used to seize our goods and we spent a lot of money and time to get them back. But under this administration police no longer harass us. So with the little money we make we have rest of mind.”

And there is an acknowledgement that there has generally been more freedom of expression under the Weah government, though the UN has expressed its concern about attacks on several journalists in the run-up to the vote.

But the 46-year-old vendor, who is a qualified accountant, too supports the establishment of a court, saying he would have a doctorate by now if it had not been for the wars: “Let them bring the court to hang all of them.”

Mr Sonyah hopes that whoever is voted into the presidency, they will listen to the wishes of the people and MPs and support the push for crimes of the past to be tried to ensure a brighter, corrupt-free future for Liberia.

“Peace without justice is like tea without sugar,” he says.