OBITUARY: Dumiso Dabengwa – December 6, 1939 – May 23, 2019

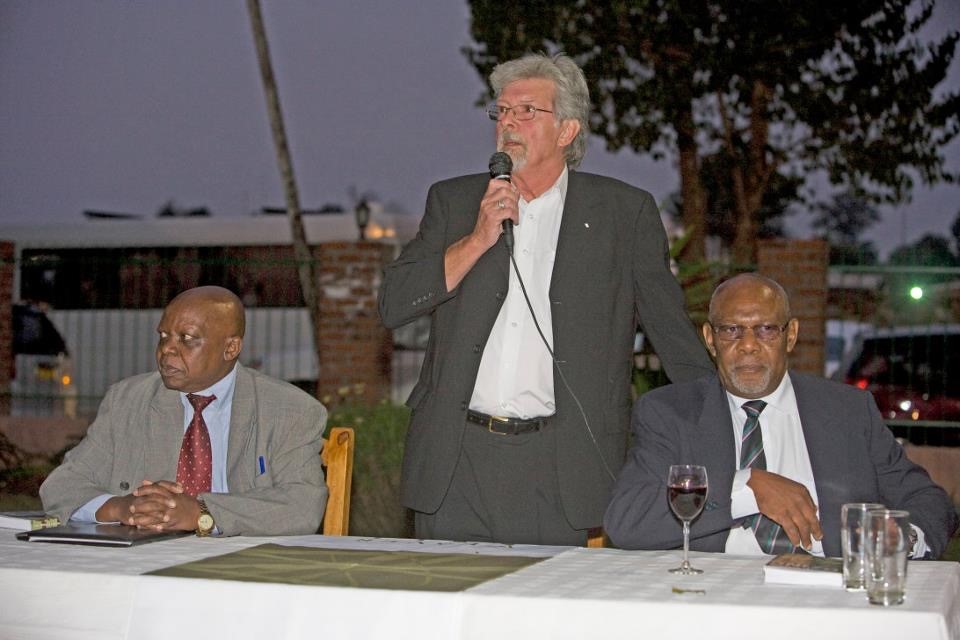

ON THE night of August 15, 2011, I attended the launch of Wilfred Mhanda’s (nom de guerre Dzinashe Machingura) memoir, Dzino: Memories of a Freedom Fighter in Harare. Mhanda was an important figure in Zimbabwe’s independence struggle – particularly for his role in the formation of ZIPA and the crafting of the Mgagao Declaration in 1975. I had recently commenced researching a scholarly biography of General Solomon Mujuru (nom de guerre Rex Nhongo), another major actor in part of the Zimbabwean liberation struggle, who crossed swords with Mhanda in the mid-1970s, resulting in momentous change in the character and direction of ZANU’s contribution to Zimbabwe’s independence.

“Make sure you interview Dumiso Dabengwa about General Mujuru,” my interviewees repeatedly counselled me at the inception of my research. Consequently, Dabengwa was high up in my list of potential interviewees. As I chatted away, in the cool of the August evening, with the genial Irene Staunton, Mhanda’s publisher at Weaver Press, Dabengwa suddenly arrived at the book launch venue. “That’s Dumiso Dabengwa over there,” I remarked excitedly. “Oh yes, he is the discussant,” Staunton pointed out.

I resolved to approach Dabengwa, at Mhanda’s book launch, about the possibility of interviewing him about Mujuru. I had met Dabengwa many years before but did not engage in any meaningful conversation with him then, so I was certain he would have no recollection of me. Dabengwa was a tad taciturn when I walked up to him and introduced myself. But my mentioning of Mujuru’s biography thawed Dabengwa’s reticence. He shared an amusing story about Mujuru, after which he uttered: “Come to Bulawayo next week and we can speak properly about Rex.” We set a date, exchanged mobile phone numbers and parted ways.

Unbeknown to Dabengwa, his good friend and political ally Mujuru was living out the final hours of his life in Beatrice, where he owned a farm. Mujuru allegedly died in a housefire on his farm, on the night of Mhanda’s book launch. Two weeks later, I travelled to Bulawayo to meet with Dabengwa. He was downcast because of the loss of his friend and pessimistic about a political future that did not include Mujuru. We bonded over the loss of Mujuru. Dabengwa always had time for me after August 2011. “Come to Bulawayo” was his standard refrain, whenever I contacted him seeking clarity on a current or historical subject he was knowledgeable about.

Dabengwa also recognised the worth of academic research on Zimbabwe’s politics and history. Dabengwa had a good brain, but he was not easy to interview. He often paused to consider, extremely carefully, his answers to my interview questions. I would watch him, frustrated at times, as his mind rapidly sifted through what he could and could not say about a subject. Dabengwa was steeped in the art of intelligence since 1964, when he first went to Moscow for intelligence training by Russia’s Committee for State Security (KGB). To pin Dabengwa down, I learned never to engage him without first constructing highly particularised questions. I dredged up specific narratives, the names of pertinent key actors and places, dates of precise events, and would produce provocative clippings from archives, so as to disarm him and get him to open up in productive ways. I knew I had been found out when Dabengwa asked, in his usual soft tone, on an occasion before we began an interview: “Have you done your homework again?”

Dabengwa died on May 23, 2019. Three days later, Phathisa Nyathi wrote, in The Sunday News, a detailed and useful obituary, focusing on Dabengwa’s early life and activism, and his focal contribution to Zimbabwe’s liberation as a soldier and an intelligence czar. However, Nyathi had only this to say about Dabengwa’s role in Zimbabwe’s independence transition: ”Dabengwa attended the Lancaster House talks in 1979 and returned home to effect the brokered ceasefire.” In so doing, Nyathi underplayed Dabengwa’s weighty role at Lancaster House, in the perilous 1979-80 ceasefire and in the crucial early post-independence phase of military integration that laid the foundation for the Zimbabwe National Army’s (ZNA) emergence.

Worse still, prevailing official nationalist accounts entirely omit Dabengwa’s significance in the history of the 1979-81 foundational state-making years. For instance, during Emmerson Mnangagwa’s 2018 presidential election campaign rallies, Zimbabweans were repeatedly told that Mnangagwa was the figure central to the ceasefire’s management and subsequent military integration of ZIPRA, ZANLA and the former Rhodesian army. Such uses and abuses of the early history of the Zimbabwean state in the making were repeated in the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC) documentary ‘President ED Mnangagwa: The Full Story’, broadcast in April 2019.

Dabengwa – not Mnangagwa – was integral to the ceasefire negotiations and initial state-making at Lancaster House, in the ceasefire’s execution and in the foundational military integration. First, in the Lancaster House talks, whilst the political principals (Joshua Nkomo, Robert Mugabe, Ian Smith, Abel Muzorewa and Peter Carrington) haggled over the political and legal architecture of independent Zimbabwe, military negotiations, the ceasefire arrangements and construction of consensus on military integration precisely, were conducted by Dabengwa, the ZANLA commander Josiah Tongogara, General Peter Walls of the Rhodesian army and the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s (FCO) Robin Renwick. The British army’s Major General John Acland and Brigadier Adam Gurdon, a military intelligence figure, were observers in the ceasefire negotiations. After Dabengwa, Tongogara and Walls negotiated the independence ceasefire, with Renwick as mediator, they all acquiesced to travel to Rhodesia to jointly implement the ceasefire.

I met with Gurdon on June 19, 2012, to discuss the 1979-1980 ceasefire. We talked in an agreeable music room belonging to the fêted English composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, Gurdon’s son-in-law. “Some of Andrew’s greatest shows were composed on that piano right there,” Gurdon crowed. Gurdon spoke of Dabengwa at Lancaster House in appreciative terms: “He was a Nkomo man. He was measured in the way he carried himself. You could tell he had good training. He thought quite deeply about things and reached out to Walls and Tongogara.” Tongogara, unlike Dabengwa, showed little allegiance to civilian authority, that is Mugabe. Thus, whereas Mugabe and the Zanu political leadership at Lancaster House retained distrust of the Rhodesians and continued to see Nkomo and ZAPU as a mortal enemy, Tongogara accepted Dabengwa’s open hand.

Renwick commented that just before Tongogara left Lancaster House, the ZANLA commander held a secret meeting with Nkomo and Dabengwa. At that meeting, Tongogara made it clear that he wanted the independence transition to work and that he did not want fighting between ZANLA and ZIPRA. Tongogara also preferred that Zanu and ZAPU contest the independence election as a single front. Dabengwa concurred with Renwick’s narration of events but he went one step further; Dabengwa maintained Tongogara expressed to him that he would have wanted Nkomo – not Mugabe – to lead the resultant independence government. Tongogara never made it alive to Rhodesia. He died in a car accident in Mozambique on December 26, 1979.

Dabengwa was in Zambia when he learned of Tongogara’s demise. He elaborated his thoughts and actions upon the news of Tongogara’s death: “Tongo and I had arranged at Lancaster [House] to fly together to Salisbury from Lusaka, after we had explained the [ceasefire] agreement to the soldiers. I went to Zambia to do that. I was now waiting for Tongo in Lusaka while he was in Mozambique. He was taking long. Nkomo sends for me and tells me Tongo is dead. It was sudden and suspicious. I said to Nkomo, ‘I’m no longer going for the ceasefire. Masuku can do it, if you want to carry on, this is too suspicious. Nkomo said no, you must go. The British also sent messages that said it was you Dabengwa and Tongo who negotiated the ceasefire with us, so you have to be there.’ I went [to Salisbury] because of Nkomo and the British.”

Implementation of the ceasefire agreement was led by a structure called the Ceasefire Commission (CC). The CC was composed of Dabengwa (ZIPRA), Acland (Commonwealth Monitoring Force commander), Gurdon (Commonwealth Monitoring Force Chief of Staff), Andrew Parker Bowles (Commonwealth Monitoring Force Senior Liaison Officer and Ceasefire Commission Secretary), Bertie Bernard (Rhodesian Army) and Peter Petter-Bowyer (Rhodesian Air Force). Nhongo (ZANLA), who was in Mozambique throughout the Lancaster House independence talks, replaced the deceased Tongogara on the CC.

The ceasefire agreement stipulated that all cross-border military undertakings by ZIPRA, ZANLA and the Rhodesian army were to cease after midnight of December 21, 1979, and the truce itself came into force at midnight on December 29. From December 29 to January 4, 1980, armed ZIPRA and ZANLA were all required to enter the nearest of 16 Assembly Points that were mostly located along Rhodesia’s periphery and accessible through 23 Rendezvous Points (RVs), except for the APs Romeo, Quebec, November, Lima, Kilo, Echo and Charlie, which were accessed directly.

There was profound hatred between ZIPRA, ZANLA and Rhodesian army rank and file, after approximately a decade of armed conflict between them, making the ceasefire a risky exercise. Indeed, on several occasions the ceasefire almost collapsed for a range of reasons such as provocation of ZANLA and ZIPRA by Rhodesian forces, clashes in joint ZANLA and ZIPRA Assembly Points and supply shortages. Whenever an incident dangerous to the ceasefire arose at a ZIPRA or ZANLA-ZIPRA Assembly Point, Dabengwa (assisted by Lookout Masuku and Ben Mathe) flew into the heat of the action with Commonwealth Monitoring Force (CMF) monitors to defuse the crisis. Nhongo (assisted by Josiah Tungamirai and Mark Dube) had similar responsibility on the ZANLA side.

The ceasefire was a taxing time for Dabengwa because the Assembly Points were powder kegs, ready to be set off by the slightest provocation or grievance, as a CMF monitor remembered: “The ZIPRA chaps complained about lack of meat and were about to leave the Assembly Point. So we quickly improvised by asking the local game ranger if they could shoot an elephant. They shot two elephants but it turned out only half the ZIPRA chaps liked elephant meat. They wanted beef. We had to bring in Dumiso to prevent a mutiny.”

The independence transition, which began with a ceasefire in late December 1979, climaxed with inclusive elections from February 27 to 29 in 1980 and formally ended with an independence ceremony on 18 April. That the ceasefire held throughout this period was in no small measure due to the leadership and far-sightedness of Dabengwa and his co-negotiators, first at Lancaster House and later as part of the CC.

After independence, the CC ceased to exist and a new military structure called the Joint High Command (JHC) came into existence. The JHC existed from April 1980 to August 1981 and in this period it managed the foundational integration and training of ZANLA, ZIPRA and the Rhodesian army into the ZNA. In 1980, the JHC was comprised of Walls (chairperson), Dabengwa, Sandy Maclean (Rhodesian army commander) and Nhongo. The JHC administered military integration in consultation with the initial British Military Advisory and Training Team (BMATT) commanders Patrick Palmer and Rupert Smith. Dabengwa and the five commanders on the JHC reported to Mugabe, who was both Prime Minister and Minister of Defence in 1980.

Walls left the ZNA towards the end of 1980, leaving Dabengwa, Nhongo, Maclean, Palmer and Smith as the early integration leaders. When the JHC was disbanded in August 1981, Dabengwa chose not to pursue a career in the military, leaving Nhongo to become head of the army and Maclean the overall commander. For a matter of months in 1981, Mnangagwa chaired JHC sessions, in order to break growing political deadlock on the JHC. BMATT archival documents show that Sydney Sekeramayi also sometimes chaired JHC meetings. It follows that those primarily responsible for the extremely complicated and fractious foundational military integration were the four mainstays on the JHC: Dabengwa, Nhongo, Maclean and BMATT.

From the Zimbabwean military leaderships, nobody contributed, rightly or wrongly, more to both the independence ceasefire negotiations, planning and implementation, and to the foundational military integration, than Dabengwa. In both these specific regards, Dabengwa was peerless because Tongogara’s story ended at Lancaster House, Walls left the ZNA in disgrace early on, and Nhongo and Maclean were not part of the ceasefire talks and planning at Lancaster House.

Miles Tendi is an associate professor of politics at the University of Oxford