PRETORIA, South Africa – Names will always be like that. Like handles with which we can hold personalities, heroes and villains alike, and understand the tragedies and comedies of their lives.

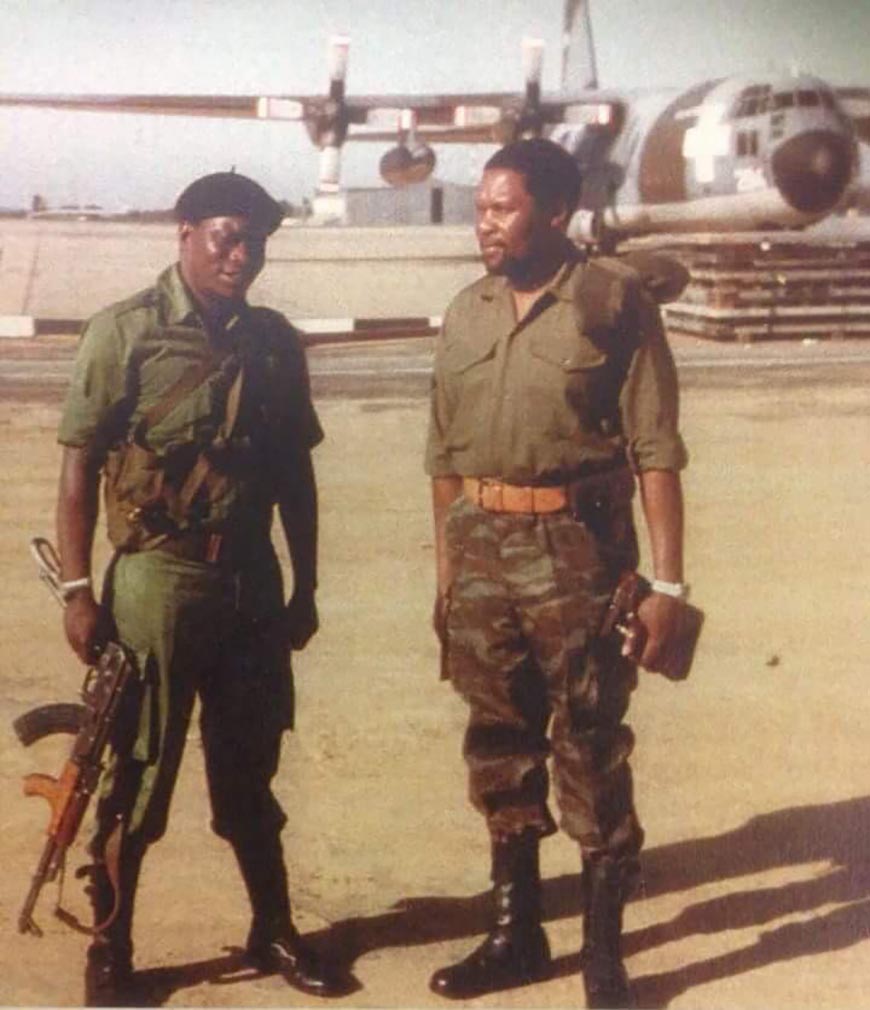

Ruzambu, the thin reed, was the sickly boy that Maidei gave birth to under the Msasa tree in Chikomba. He gained a reputation for fighting many fights and losing most of them against other boys. As Rex Nhongo, he was the true he-goat of a guerilla commander. He expired many Rhodesian Forces soldiers and black villagers that were identified as sellouts. The Rhodesian soldiers called him “Missed” for the reason that every time they cornered him in the bush, their bullets missed him. A British soldier described him as the “Black Pudding with a Killer Instinct” for his warlike deportment. They also titled him the “Small Big Man” for the power he carried in his otherwise small bodily frame.

The guerillas referred to him as “Problem” because whenever he was on the front, the Rhodies troubled the forests hunting for him, and haunting the freedom fighters in their hideouts. Right in the heat of gunfire, he used to move around the trenches distributing twists of dagga and dealing a big stick on the buttocks of guerillas that were not firing straight at the Rhodies. Enos Nkala crowned him “Tshaka” for the warrior habits he exhibited in battle and outside.

General Solomon Tapfumaneyi Mujuru is the regal name he wore as the moneyed and influential tycoon of a “Kingmaker” in Zimbabwe. He was one of the very few, if not the only person that looked Robert Mugabe in the eye and suggested leadership change in the party and the country. He spoke with an embarrassing stutter that marked him out as a man given to battles not conversations. His frenzied accumulation of big wealth was at the same time the love for money out of a “sense of entitlement”, and also a fear of poverty that he knew well from childhood.

Ever the guerilla operator, at the very height of the tensions between his party Zanu PF and the Movement for Democratic Change, the General did not mind sitting in tense politburo meetings by day and by night summoning the opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai to his posh offices in Gunhill to chew bone with him about the condition and future of the country, and this as he downed flagons of Johnnie Walker whisky. The General was what is called a high functioning alcoholic. Alcohol and women were his second nature. Frequently, he took his meals with concoctions of aphrodisiacs. The crowning act of his womanising is when he was caught butt-naked in bed with the wife of a junior soldier. The night he was killed he had a young lady companion that the killers did not spare.

Vice President Constantino Chiwenga lives with the wound of a strong belief that the General was bedding his first wife. Car keys and marked army jackets are part of the collection of items kept by traumatised husbands after the General had visited their matrimonial bedrooms. He had friends that loved him dearly and enemies that feared him intensely. Circumstances around his horrible death in a farmhouse fire show that some were friends and enemies at the same time and someone close gave the General the kiss of Judas. He was killed rather easily because he was fearless. An inside sympathiser privy to the dark plot sent a timeous telephonic warning that was fearlessly and most strangely ignored. A group of killers ambushed, shot and killed him, and then burnt his body in an attempt to erase evidence. Those who sent the assassins obviously feared and loathed him. His became one of the many mysterious and suspicious deaths of key ZANLA and Zanu PF figures. Not to mention political opposition figures.

It has taken what I observe to be one scholar’s monstrous intellect to piece together the spectacular tale of the rise and tragic fall of a great soldier that lived his life and did his work with compelling gravitas. The scholar gathered telling testimonies of senior securocrats, spies, Mujuru’s family, reports of private investigators and confessions of intimate sources to weave together a narrative that is a must read for anyone that wants to see through Zimbabwe’s past and present. The book is a movie script, except that the characters are real and known men and women.

The General Stuff of Tragedy

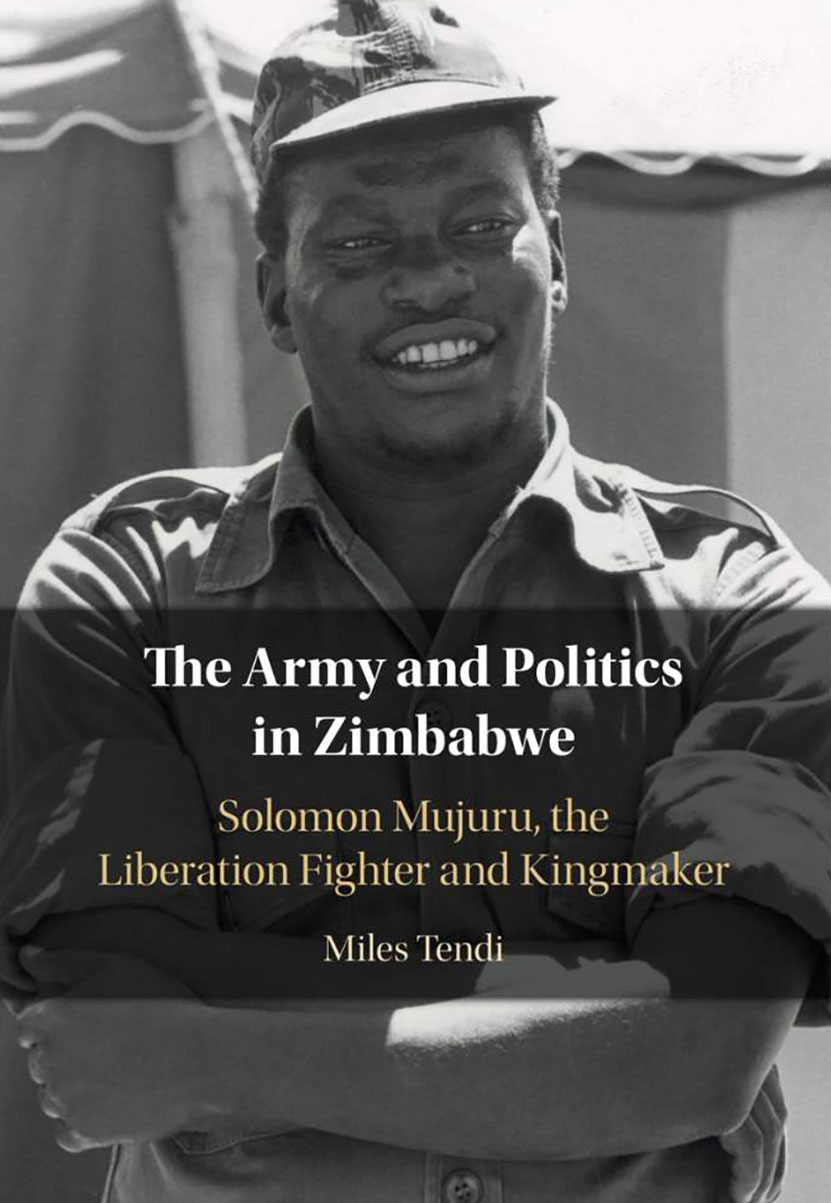

In the book, The Army and Politics in Zimbabwe: Mujuru the Liberation Fighter and Kingmaker (2020), Oxford University based scholar, Blessing-Miles Tendi, combines fine social science and a pulsating art of story-telling to capture the tragedies and comedies of Mujuru’s life. The book is both a compelling scholarly account and a bewitching story. Through the life story of Mujuru, before, during and after the war of liberation, Tendi leads the reader into the bloody and dark history of Zimbabwe and the culture of political evil that infected the politics of the country. The way leaders were toppled and assassinated in the struggle, how dear friends betrayed each other, how good people died and evil personages survived is the true stuff of tragedy. One might proffer a dark guess that Zimbabwe’s war of liberation was a game refereed by the devil. All that could go wrong went wrong and the wrong people were in the right place shepherding the future of the country in a dark direction on a road paved with tears, blood and the bones of heroes

The reader that takes on reading this book must prepare for crying, especially if they love Zimbabwe, and for royal laughs if they are not immune to mirth in the midst of tragedy. In this book Tendi fights, like a true iconoclast, disputing false claims by powerful men and overturning misrepresentations of many scholars and journalists. To me, one of the most challenging fights Tendi picks and wins is the fight against himself, the calculated and impressively scholarly way in which he obviously admires Mujuru but hammers his book away from slipping into poetic hagiography.

Miles’ admiration of the General does not prevent him from disclosing the tragic way in which as army chief he cultivated a culture of massive corruption and cozenage that continues to haunt Zimbabwe today. When guerillas were being marshalled from the bush into Assembly Points, the General kept thousands of ZANLA bandits in the bush and the villages, and later used them to campaign for Zanu PF brandishing AK47s. The same bandits killed, raped and robbed with impunity.

If it was a lazy rumour before, Tendi supplies the evidence that it is Mujuru that enabled Mugabe to lead Zanu PF and eventually Zimbabwe. Mujuru elevated Mugabe to leadership against fierce resistance from powerful Frontline Heads of States such as Samora Machel who believed that Mugabe was “Smith’s Man,” a Rhodesian spy. Josiah Tongoogara did not want Mugabe near ZANLA. He believed Mugabe was a sellout. Tongogara also did not want ZANU to contest the independence elections outside a union with ZAPU, a political union that could have spared Zimbabwe many tragedies including the Gukurahundi genocide.

The young cadres of the Zimbabwe People’s Army (ZIPA) laid down their lives resisting the leadership of Mugabe. Selectively, Mujuru saved some and handed over others, some his dear friends, to incarceration and slaughter. Mujuru’s enchantment with Mugabe was based on two reasons: Mugabe was his nephew, and Mujuru had respect that bordered on fear for educated and knowledgeable people. Mujuru’s good soldierly character did not prevent him from sinking to clanism, tribalism and homeboyism. The bloodline and the way Mugabe performed his education, speaking English with an Edwardian accent mesmerised Mujuru, a scarcely educated rural boy that by all accounts seems to have wanted the very best for Zimbabwe.

When Machel detained Mugabe to keep him away from the guerillas in Mozambique, Mujuru would nicodemously visit the detainee by night to brief him as his leader. This went on until Machel accepted Mugabe. That Mugabe, through his long stay in power disappointed Mujuru, is now public knowledge. What is not public knowledge is that Mujuru spent many years in Zanu PF trying, day and night, to negotiate and navigate Mugabe out of power. He died trying, and of trying.

Even in his frustration with Mugabe and his rule, the General remained a master of dark humour. Once, Mugabe’s jet got into a dangerous emergency but the situation was saved before tragedy. The General is said to have cried that the thing had survived otherwise it was, to his wishes, supposed to die with everyone on board. That is how far relations had soured between king and kingmaker.

When Mujuru was killed, out of their own sense of Ubuntu, the opposition leaders Morgan Tsvangirai and Authar Mutambara, separately approached Mugabe to commiserate with him over the loss of the General. What they encountered is a nonchalant Mugabe who ruled out foul play before any investigation. The then Minister in the President’s office in charge of intelligence approached Mugabe with some telling intelligence concerning circumstances around the General’s death. An angry Mugabe lashed out: “He was a drunkard!” Didymus Mutasa left, he says, knowing that there “was more than meets the eye.”

It was Grace Mugabe who told the mourners amidst her weeping and wailing at the Mujurus that some unnamed people, “when they don’t want someone, they kill that person.” President Mugabe made the freshly widowed Joice Mujuru the Acting President. Later during the inquest that sought to “probe” the truth around the General’s demise, Mugabe would frequently call the widow out of court for urgent discussions that included a telling whisper to her that she should forget the inquest and prepare herself to take over from him as President. It was all a poor show in dissembling.

In Zanu PF high places, the General’s death was received with a coldness that strangely resembled celebration. Much the same way in which Mujuru himself is reported in the book to have received the news of the death of Tongogara with a cut and dry “thank you, Comrade” to the British soldier who broke the news to him.

The General was not well-liked, such figures as Chiwenga, Vitalis Zvinavashe, Josiah Tungamirai and Emmerson Mnangagwa hated and feared him. From Herbert Chitepo through Tongogara up to Mujuru, not counting numerous other unsolved and suspicious deaths, Zanu PF is clearly an organisation whose history breathes the oxygen of choreographed fatal accidents. The victims of the accidents died while up to something big. Tongogara was busy trying to influence the ZANU and ZAPU union before the independence elections while Mujuru was occupied with pressuring Mugabe to retire.

The General and Gukurahundi

The 5 Brigade was deployed when Mujuru had been sent on a military education leave in Pakistan. The leave was also a ploy by Mugabe to reduce his influence in the Zimbabwe National Army. Former commanders of the 5 Brigade told Tendi that Gukurahundi and its project were the responsibility of Mnangagwa and Mugabe. Mnangagwa came up with volatile “politicised intelligence” reports to convince Mugabe to crush ZAPU or his government would be toppled. The political intention of Gukurahundi was to finish off ZAPU and occasion one-party state rule in Zimbabwe.

On his part, Mujuru supervised the persecution of former ZIPRA cadres within the National Army, forcing some to retire early and others to desert in fear for their lives. Tribal hatreds were a huge elephant in the room during the guerilla war and after in the Zimbabwe National Army. Gukurahundi became an opportunity, also, to feed enduring tribal grudges.

During the war, Tongogara might have performed himself as a Karanga boy but his original South African Xhosa roots were invoked against him. Against Mujuru were durable suspicions that he was actually still a ZIPRA guerilla deep inside, and he came under pressure to prove his loyalty to Zanu PF by punishing ZIPRA cadres in the army. Secretly, he saved a few of them from incarceration and death.

Looking at the evil of Gukurahundi and the political assassinations, I feel it with Tendi that the people that walked out of colonial prisons and the bush war were supposed to pass through rehabilitation before assuming military and political roles in Zimbabwe. Some very unwell and disturbed people are occupying positions of power in the country. The evil political culture of assassinations and other eliminations through slow poisons is an evil legacy that keeps being restored and leaders will continue to eliminate each other until the last one standing if good men and women do not disrupt their evil enterprise. – [email protected]

Published by Cambridge University Press, the book is available in Zimbabwean bookstores Innov8 and Weaver. You can purchase the hardback on Amazon, and a more affordable paperback option is available on the publishers’ African branch website