PRESIDENT Emmerson Mnangagwa is serving his second and last term, which ends on September 4, 2028, according to the Constitution of Zimbabwe.

There is a strong push from a well-resourced Zanu PF faction aligned to President Mnangagwa, to extend his term to 2030 with some advocating that he should be given a full third term. No logical reason has been presented in support of the desire to extend Mnangagwa’s term.

Zanu PF national political commissar Munyaradzi Machacha is reported to have said that his party plans to extend Mnangagwa’s current term by postponing the general election from 2028 to 2030, through a constitutional amendment which does not require approval by Zimbabweans through a referendum.

The Zanu PF chairman for Harare province Godwills Masimirembwa further explained that the “proposed extension [of the president’s term] does not violate constitutional term limits as it only postpones elections to 2030 without altering the two term cap.”

Is this legally possible? The short and direct answer to that question is NO! It is legally impossible to do so without creating a constitutional and legitimacy crisis of unprecedent propositions, with potential to plunge Zimbabwe into serious political instability and catastrophic repercussions on the SADC region.

The term of office for Members of Parliament (MPs), the president and municipal councillors is constitutionally fixed at five years. The timing of a general election for the president, MPs and councillors is governed by section 158 (1) of the constitution, which states that “a general election must be held so that polling takes place not more than— (a) thirty days before the expiry of the five-year period specified in section 143.”

Therefore, the next general election for the President, MPs and Councillors is due by September 4, 2028. To postpone this election, parliament will need to amend both section 158 and section 328 (7) of the constitution. Let me explain why.

Postponement of the next general election without amending section 328 (7) will create a constitutional crisis. Ordinarily the amendment of section 158 of the constitution of Zimbabwe does not require the holding of a national referendum provided the effect of the amendment is not to extend the term of office of the incumbent president, MPs and councillors. If an amendment of section 158 of the constitution is aimed at postponing any other general election other than the next one, such an amendment must follow the procedures set out under section 328 (3)-(5) of the constitution, which essentially requires the amendment bill to be supported by a minimum of two thirds majority of the members of each of the two legislative houses.

For example, if the current parliament decides to postpone the 2033 general election to 2035 by increasing the term of office of the president and parliament from 5 to 7 years, they will introduce a constitutional bill to amend section 158 of the constitution, and that bill shall not require approval by Zimbabweans through a national referendum. All it requires is adoption by at least two thirds majority of the members of each of the two legislative houses.

However, if the amendment of section 158 of the constitution seeks to postpone the next general election (that is due in 2028), that amendment cannot benefit the incumbent president, MPs and councillors. Put differently, a constitutional amendment that is meant to postpone the next general election in Zimbabwe cannot be applied to elongate or extend the incumbency of the current president, MPs and councillors. This is because, section 328 (7) of the constitution states that:

“Notwithstanding any other provision of this section, an amendment to a term-limit provision, the effect of which is to extend the length of time that a person may hold or occupy any public office, does not apply in relation to any person who held or occupied that office, or an equivalent office, at any time before the amendment.”

A constitutional amendment that postpones the 2028 general election naturally extends the length of the time that the incumbent president, MPs and councillors will occupy these offices. Therefore, such a constitutional amendment is in fact an amendment of a term limit which cannot be applied to benefit President Mnangagwa or current MPs by virtue of section 328 (7) of the constitution.

In fact, any constitutional amendment to postpone the next general election, that is not accompanied by an amendment of section 328(7) of the constitution will collapse the government and create a constitutional crisis of unprecedented proportions.

If Zanu PF amends section 158 to postpone the next general election to 2030, it means that when the term of the current government ends in September 2028, Zimbabwe will not have a government for two years until 2030. The only way this situation can be avoided is if the postponement of the next general election is also accompanied by a constitutional amendment of section 328(7) of the constitution to allow the postponement to benefit the incumbent president, MPs and councillors. But an amendment of section 328(7) requires approval by Zimbabweans through a national referendum by virtue of section 328(9) of the constitution.

Therefore, it is constitutionally impossible to postpone the next general election as a way of extending President Mnangagwa’s term to 2030. Such a proposition is not only absurd but is a dangerous suggestion that could plunge Zimbabwe into a constitutional crisis that has never been witnessed anywhere in the history of modern democracies. Campaigning to implement such a proposition is in itself a serious national security threat.

In an effort to analyse and explain the behaviours of modern autocrats and despots, Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way developed the political science theory of “competitive authoritarianism.” The two esteemed scholars argue that the strategy of modern autocrats is to maintain democratic institutions and structures on paper but in practice subvert democratic norms and standards. For example, contemporary dictators ritualistically hold elections regularly as required by the constitution, but those elections are rigged in favour of the incumbent.

Contemporary dictators maintain constitutions which guarantee judicial independence, but they often find creative ways of controlling judges and courts. This type of authoritarianism is what Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way call “competitive authoritarianism”. In his article “The Contemporary Crisis of Constitutional Democracy” Martin Loughlin describes such regimes as “defective democracies” where there is competition (often-through elections and deliberations in legal courts) but the competition is always deliberately skewed in favour of the incumbent.

Mnangagwa is a competitive authoritarianist. This is what he meant when he famously described himself as a “constitutionalist.” Why do I say this? Mnangagwa succeeded former President Robert Mugabe through a military coup which, however, was carefully choregraphed as a peaceful and democratic transition demanded and driven by the popular will of Zimbabweans and conducted in compliance with the constitution.

The Constitutional Court of Zimbabwe in the case of Liberal Democrats v President of the Republic of Zimbabwe, held that the transition from Mugabe to Mnangagwa was constitutionally compliant. This is notwithstanding overwhelming evidence demonstrating that Mugabe was forced to resign through a military coup, and thus, the transition could never be constitutionally compliant.

In my academic article “The Zimbabwean Constitutional Court as a key site of struggle for human rights protection” I presented the argument that, consistent with competitive authoritarianism, Mnangagwa’s unconstitutional rise to power in 2017 was clothed with a veneer of constitutional legitimacy by the Constitutional Court through its decision in Liberal Democrats v President of the Republic of Zimbabwe.

Mnangagwa’s reign, since he came to power in 2017 demonstrates firm commitment to competitive authoritarianism. For example, he advocated for the legal abolishment of the death penalty, yet he has not done much to stop extra judicial killings of his political opponents. His government has maintained the constitutional right to protest but security agents have made sure that no-one exercises that right.

Instead of banning the opposition (like what other dictators who include Macky Sall of Senegal did), Mnangagwa has chosen to infiltrate the opposition and now controls it. Poor leadership and lack of democracy in the opposition under Nelson Chamisa created extensive dissatisfaction and divisions amongst opposition members, and this catalysed Mnangagwa’s bid to take over the opposition.

Mnangagwa has said he will respect the constitutional term limits, but he has allowed his supporters and cabinet ministers to campaign for the extension of his term. Typical of competitive authoritarianists, the plan might be for Mnangagwa to appear as if he is being pressured by the citizens to extend his term when in fact it is him who wants the term to be extended.

Consistent with his style as a competitive authoritarianist, Mnangagwa’s likely first option is to pursue a third term through means which appear on paper to be consistent with democracy. This is the only way he can claim legitimacy in the eyes of the regional and international community. A veneer of legitimacy will be necessary for him given the dynamic geopolitics both in the region and internationally.

It is unlikely that, as a first option, Mnangagwa would pursue a third term through means that are brazenly unconstitutional and undemocratic. If Parliament amends section 158 of the constitution to postpone the elections from 2028 to 2030 as suggested by Zanu PF and Masimirembwa, Zimbabwe will not have a legitimate government from September 4, 2028. The current president, MPs and councillors would be illegitimate office bearers if they attempt to remain in office beyond September 4, 2028, unless parliament also amends section 328(7) of the constitution, and such an amendment must be ratified by Zimbabweans through a national referendum.

My thesis is that Mnangagwa seeks to secure a third term through a constitutional coup which avoids a referendum, but which appears consistent with popular democracy. He may not afford to openly disregard the constitution as that will create a legitimacy crisis which could make him more vulnerable politically. This is why I am still convinced that he is contemplating to secure a third term through temporary succession. Some analysts have counter argued that temporary succession is too risky for Mnangagwa. While I agree with that view, it should be noted that, of all the competitive authoritarianist options on the table, temporary succession appears the safest route for Mnangagwa’s third term bid. All other avenues will require ratification by Zimbabweans through a national referendum and Mnangagwa is unlikely to win that referendum.

As already suggested by Zanu PF, the third term campaigners are working to avoid the referendum at all costs. An attempt to secure a third term through temporary succession appears to be more likely. However, I do not rule out other possibilities.

The stakes are too high for a referendum. It is my firm belief that those pushing for a third term are most likely going to opt for a party-driven succession process which utilises sections 91 and 101 of the constitution.

The next presidential election is due in 2028, according to the constitution of Zimbabwe. In order to be eligible to contest in that election, a candidate must meet the requirements set out in section 91 of the constitution, particularly sub-section 2 which states that: “(2) A person is disqualified for election as President or appointment as Vice President if he or she has already held office as President under this Constitution for two terms, whether continuous or not, and for the purpose of this subsection three or more years’ service is deemed to be a full term.”

Mnangagwa may still be eligible to contest in the 2028 presidential election if he avoids serving his current term to the full. In terms of section 91(2) of the constitution cited above, a person is considered to have served a full term if he or she has served for three or more years as president.

Mnangagwa’s current term began on September 4, 2023, when he was sworn in by the Chief Justice in terms of section 95 of the constitution. Therefore, he will only be deemed to have served a full term if he remains in office beyond September 3, 2026.

If he resigns prior to September 4, 2026, Mnangagwa will not be deemed to have served a full term in terms of section 91(2) of the constitution and, therefore, he will be eligible to contest in the 2028 presidential election.

His resignation will trigger section 101 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe which states that: “a) the Vice President or, where there are two Vice Presidents, the Vice President who was last nominated to act in terms of section 100, acts as president until a new president assumes office in terms of subsection (2); and (b) the vacancy in the office of President must be filled by a nominee of the political party which the president represented when he or she stood for election.”

Section 101 of the constitution was amended in 2021, perhaps as part of laying the foundation for securing a third term for Mnangagwa.

The original provisions of section 101(1)(a) of the constitution stipulated that in the event of the President’s resignation, the first vice president would assume office as president until the expiry of the former president’ term.

That would mean that, in the event of Mnangagwa’s resignation, the current first vice president Constantino Chiwenga would automatically assume the office of president until the next election in 2028.

This is no longer the case, as a result of the amendments to section 101 effected in 2021. Under the current provisions of section 101(1) of the constitution, in the event of Mnangagwa’s resignation, one of the two vice presidents will step in and act as president until Zanu PF nominates a candidate who will be sworn in as president to serve until 2028.

Whether it is Chiwenga or Mohadi who will act after the president’s resignation is politically immaterial. This is because Zanu PF is entitled under section 101(2) of the constitution to nominate the president’s replacement within 90 days.

This does not mean that Zanu PF has to wait for 90 days to do that. The nomination can be done on the same day that Mnangagwa would have resigned.

It appears to me that those campaigning for Mnangagwa’s third term have been meticulously preparing for this strategy when they introduced Resolution No 2, which was adopted at the Zanu PF annual conference in 2024.

It states that the “party and government should establish a comprehensive framework that ensures the operationalisation of the principle of party supremacy over government.”

In order to understand the significance of this resolution, it is critical to remember that even after resigning from being President of the Republic, Mnangagwa will remain the first secretary and therefore, the leader of Zanu PF.

He can use that position to influence the party’s decision on the nominee to serve as president until 2028. That nominee would merely be Mnangagwa’s proxy.

Zanu PF Resolution No. 2 (cited above) paves way for the adoption of various regulations and policies by Zanu PF which will enable the first secretary of the party (Mnangagwa) to continue running the state through a proxy while waiting for the 2028 presidential election.

I make the following propositions in defence of the Constitution:

Zimbabwean civil society, academics and political parties must urgently undertake a mission to sensitise the governments and citizens of SADC member states (and the African Union), about Zanu PF’s sinister agenda to create a constitutional crisis in Zimbabwe. It must be made very clear to regional governments and citizens in the region and the continent that the impending constitutional crisis in Zimbabwe will have unprecedented repercussions on stability not only in Zimbabwe but the SADC region and thus, it is in the interests of the region to persuade Mnangagwa to respect constitutional term limits and unequivocally call off the ongoing dangerous campaign to extend his term of office.

There is an urgent need to conduct mass peaceful protests within and outside of Zimbabwe to demonstrate Zimbabweans’ disapproval of Zanu PF’s bid to subvert the constitution by extending Mnangagwa’s term.

Opposition leaders should lead from the front on this assignment! Zimbabwean media and civil society must exert maximum pressure on parliament by holding the MPs accountable for their actions regarding Mnangagwa’s third term bid. Given that the primary duty of parliament is to protect the constitution, MPs must be questioned to clarify and explain why they are said to be working on an amendment to postpone the next election without holding a referendum, as that would collapse the government in 2028 and create a constitutional crisis.

Zimbabweans from across the political and social strata must unite to form a broad-based opposition movement that is competent to defeat Mnangagwa in the 2028 presidential election, should he decide to contest in that election. This might be the only way to stop Mnangagwa’s sinister third term bid and save the constitution of Zimbabwe.

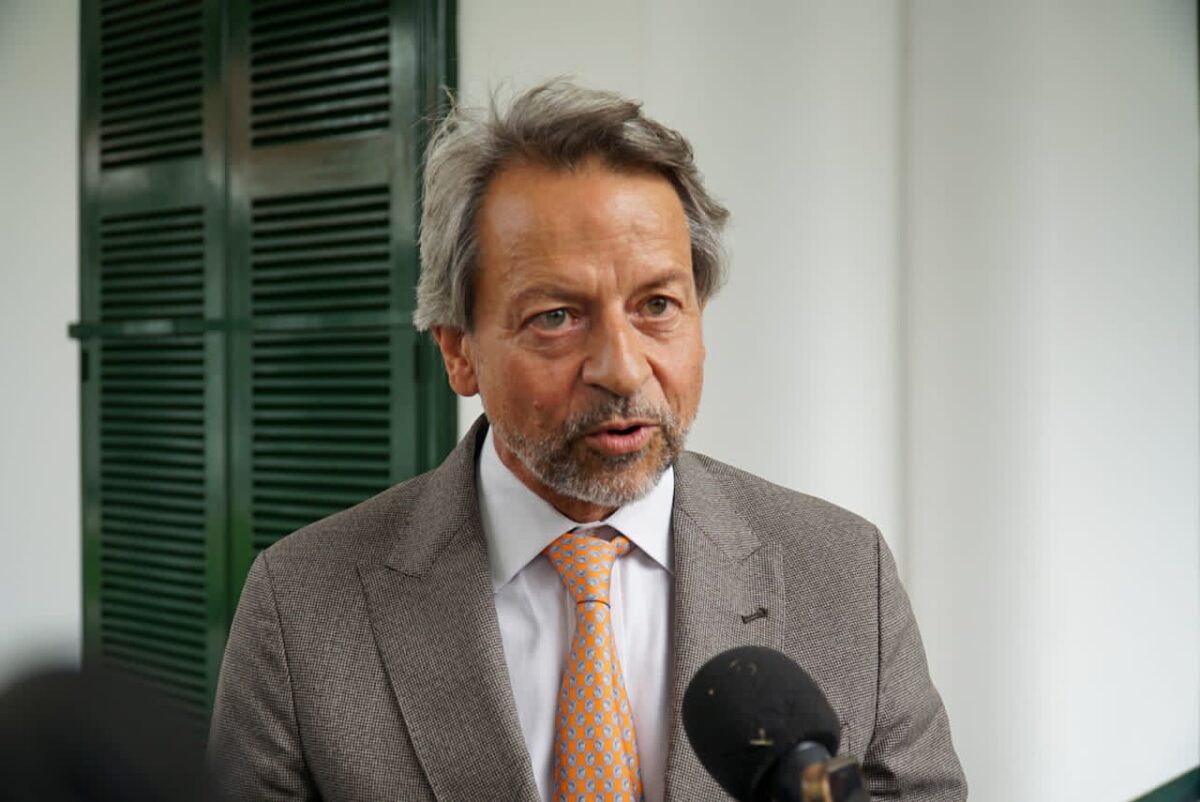

Justice Alfred Mavedzenge is a constitutional lawyer and adjunct senior lecturer of Public Law at the University of Cape Town