LONDON, United Kingdom – Britain is increasingly confident that vaccines work against the coronavirus variant first found in India, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said on Wednesday, with a leading epidemiologist saying it may be spreading less quickly than at first feared.

Johnson has warned that the emergence of the B.1.617.2 variant might derail his plans to lift England’s lockdown fully on June 21, but on Wednesday he said the latest data had been encouraging.

“We have increasing confidence vaccines are effective against all variants, including the Indian variant,” he told parliament.

Johnson last week said the extent to which the variant could disrupt the planned exit from lockdown would depend on how much more transmissible it was.

Many countries around the world, including Zimbabwe, are in panic fearing a third wave since the Indian variant was detected amid warnings it spread more easily.

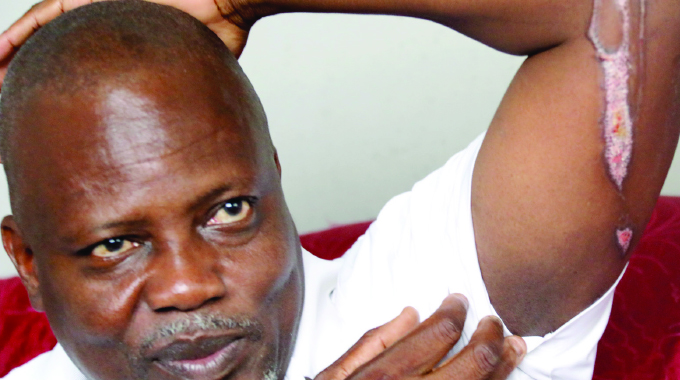

A Kwekwe resident who recently returned from India died on admission at Kwekwe General Hospital on May 12. Information Minister Monica Mutsvangwa told reporters on Tuesday that 11 contacts of the deceased individual had also tested positive for the virus.

“The nation is advised that genomic sequencing tests are being done to determine if there was an import of the Indian strain,” she said.

Neil Ferguson, an epidemiologist at Imperial College London, said there was a “glimmer of hope” from the latest data that the transmissibility of the variant might be lower than first feared.

Ferguson said the initial rapid growth of B.1.617.2 had been among people who had travelled and who had a higher chance of living in multi-generational households or in deprived areas, and the ease of transmission might not be replicated in other settings.

Ferguson told the BBC: “So first of all it’s never all or nothing with science, you gain evidence as the data is collected. The challenge we have – and just to explain to people why this is difficult, I mean we’re tracking this virus you could say ‘Well, why can’t we immediately see how it outcompetes the existing Kent variant?’– is because of how it was introduced into the country.

“It was introduced from overseas, principally into people with Indian ethnicity, a higher chance in living in multigenerational households and often in quite deprived areas with high density housing so we’re trying to work out whether the rapid growth we’ve seen in areas such as Bolton is going to be typical of what we could expect elsewhere or is really what is called a ‘founder effect’ which is often seen in these circumstances.

“There’s a little bit of – I would say – a glimmer of hope from the recent data that while this variant does still appear to have a significant growth advantage, the magnitude of that advantage seems to have dropped a little bit with the most recent data so the curves are flattening a little but it will take more time for us to be definitive about it.”

He said that while there was a “good deal of confidence” that vaccines would continue to protect against severe disease, the variant might lead to reduced vaccine efficacy against infection and transmission.

Graham Medley, a professor of disease modelling at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and a member of the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), said that while the variant was growing quickly in some places, “we haven’t yet seen it take off and grow rapidly everywhere else”.

“One of the key things we’ll be looking for in the coming weeks will be: how far does it spread outside of those areas,” he told Reuters.