ON Friday, September 6, 2019, I woke up to the news that former President Comrade Robert Gabriel Mugabe was no more. His death was something I dreaded for years as I worked to secure his well-being.

This larger-than-life figure in the history of Zimbabwe was but the embodiment of life and longevity. He even aimed to live beyond 100 years. The news of his passing came as a shock, even though he was 95 and had been unwell for some time.

The truth is, no matter how much one may psychologically prepare, death remains a dreadful and sorrowful event. So I am very sad and have not found the energy to do anything else since he died, than mourn my former leader and president.

The death of Mugabe reminded me of the manner in which comandante Fidel Castro, the Cuban leader, dealt with his impending death. He had battled and survived cancer for many years and when he knew that his end was near, he was ready and told the world that “the time was coming when I will go the way many others went before”.

Not long after this, the indomitable Castro departed on November 25, 2016. Mugabe was there to bid farewell to that iconic revolutionary. Now, it is our turn to bid farewell to our own iconic revolutionary who has now also gone the way of all on earth.

While I joined the liberation struggle in 1975, I first saw Mugabe in 1977 in Nachingwea, Tanzania, when I was one of the 5000-strong Songambele Group of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (Zanla) combatants who had just completed training under the instruction of the Tanzania People’s Defence Forces and Chinese experts of the People’s Liberation Army.

Mugabe was the leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu). He came to Nachingwea together with Dr Joshua Nkomo who was the leader of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu).

The two were the leaders of the Patriotic Front, an alliance forged just before the Geneva Conference in 1976 by Zanu and Zapu, the two liberation movements which waged the armed struggle for the independence of the former British colony of Southern Rhodesia, present-day Zimbabwe.

Mugabe spoke first after introductions by Tanzania’s Brigadier Hashim Mbita who led the Organisation of African Unity’s (OAU’s) Liberation Committee, followed by Mayor Urimbo, the Zanu Political Commissar who did some moral raising before the leaders’ speeches. Nkomo spoke last. We were dazzled by Mugabe’s intelligence, eloquence and mastery of the English language. In that regard, he was in a class of his own. Our Tanzanian instructors were equally captivated by him and remarked afterwards that it was clear that Zimbabwe should maintain the Westminster system of government, with Nkomo as President and Mugabe as Prime Minister of independent Zimbabwe.

At the time, I was pre-occupied with being a good guerrilla fighter, and I didn’t think much about it. I was not interested in politics, thinking that after the war, I would pick up my life, go back to school and integrate into civilian life. Little did I know that fate would deal me a card where my professional career would be judged on the basis of my service to Zimbabwe under the leadership of Mugabe.

When Independence came in 1980, I became an officer in the Zimbabwe National Army. Mugabe was the Prime Minister and Minister of Defence up to 1987 and later the President and Commander-in-Chief; the man who commissioned me into the officer ranks. The commissioning scroll which he signed ordered me to inter alia, “at all times exercise and diligently discipline in arms those under my command and to observe and follow such lawful orders and directives as I would receive from time to time from him or any superior officer”.

Under his leadership, the Zimbabwe Defence Forces scored successes in counter-insurgency operations in Mozambique, and in conventional warfare in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in pursuit of Pan-Africanist objectives. They were also to participate most successfully in various United Nations peace missions, including Somalia and Angola. Zimbabwean forces were recognised as professional forces; the envy of many on the continent.

The discipline which Mugabe urged on the officer corps of the defence forces is a leadership quality which he lived by. This was very evident from inter alia his strict exercise regime, diet and immaculate dressing in his own life. He was a stickler for detail who strove for excellence.

Meritocracy drove him, and he did not care much about where you came from, but as long as you were capable he would entrust you to the mission. He was a man of principle and the whole world knows that he consistently stood by his beliefs. Once he took a stand, he could hardly be moved.

He really believed in the emancipation and empowerment of the black man in Zimbabwe, Africa and even the diaspora. His views on the reform of the United Nations Security Council are well-known globally, having been the main theme of his valedictory speech to the chairmanship of the African Union in January 2016.

He believed that Africans could do anything other races could do, and this has been ingrained in the psyche of every Zimbabwean. We are free in mind and spirit. We are independent and speak our minds; we do not lie down and allow others to walk all over us. For this we should thank Mugabe who was above all a true patriot who loved Zimbabwe. Leaving the army was a most difficult time for me, but as a cadre of the struggle, you go where you are deployed.

In hindsight, however, I now consider myself to have been most fortunate to have been selected and appointed to the President’s Department in 1998. I was to work with Mugabe on a daily basis, first as the Deputy Director-General, and later as Director-General. I was to become Mugabe’s longest-serving director-general of intelligence.

My job was to brief him on security matters, and as educated and knowledgeable as the man was, I have never met such a good listener. I was not surprised to discover that Ken Flower, the late founding Director-General of the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) also recorded in his book, Serving Secretly, that of the Prime Ministers he served, Mugabe was the best in patiently listening to the reports and briefings which he was given.

Being a good listener is a most rare quality in a leader. This trait is probably what served the man well and goes toward explaining his staying power in politics.

Those who knew him well will even recall that, although he was served by many aides, he would, especially in the early years, take his own notes in important meetings, giving him the ability to address issues raised effectively. He also had a sharp mind which could store and quickly process a lot of information. I shall forever be grateful for his confidence and the support he gave to the intelligence community when I was director-general.

I thank him also for the honour he bestowed on his intelligence and security service, the CIO, each year. He never missed a single graduation ceremony.

His commitment to duty in this regard was unparalleled. It was on such occasions that he dazzled us by his intelligence and academic prowess. His performance ensured that we remained in no doubt that he was the leader of the Zimbabwean intelligence and new officers became aware that they were joining a most noble and intellectually postured and primed profession.

Such induction into the service, and the inculcation of academic and professional ethos and standards ensured the better execution of our mission, a process which on many occasions moved our country forward. I believe that these are virtuous qualities which will continue to serve our country well into the future.

In the years I served him directly on a daily basis, I was struck by the man’s love for his country, his patriotism, which came through in all he did. The country went through a most difficult period as we faced a huge backlash to the land reform programme. The issues of sanctions and the illegal regime change agenda have now been documented in various biographies of some of the players.

In his famous speech to the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 2002, his “Blair keep your England and I keep my Zimbabwe” speech was an expression of this deep love for his country and the frustration he was experiencing from the then British Prime Minister Tony Blair.

I remember one day when we flew in the presidential helicopter from Gweru to Harare in the late afternoon. I could see him survey the landscape of Zimbabwe through the window.

I followed his gaze to the African sunset, well-known for its beauty, and watched the rays of the sun dance on the savannah landscape below through the double glass fronting the windows. It was very beautiful.

We were caught in the moment and I made the remark that Zimbabwe was a very beautiful country. The former president, in his quick and witty way, remarked that this beauty and riches which lay in the land was the reason why ‘the British would not let us be!”

For Zimbabweans of course, this country is not only beautiful, but it is the only one we have got. It is the reason why thousands of heroic comrades, country men, women and children paid the ultimate price during the liberation war.

Mugabe’s patriotism also found expression in his policies. He gave meaning and content to the emancipation of his people through a whole range of policy thrusts in various sectors, especially in his early years in office where education probably stands out as the most successful.

Land reform and the economic empowerment of indigenous Zimbabweans were to define his later years in power. In 2000, he said to me at one point that he could not allow a situation where each time he drove on a major highway, he would be seized by the realisation that his people owned only the road on which he was driving and the few metres on either side of it, while most of the rich pasture and agricultural land as far as the eye could see, to the horizon, belonged to the white commercial farmers. This had to be rectified.

His achievement in this regard cannot be taken away from him. Sure, there will be debate on the impact of his policies, but Zimbabweans know that he meant well and was serious in his quest to empower them. Mugabe was a principled and very genuine person. These policies were later extended to minerals and other sectors of the economy. The death of Mugabe must also focus our minds to the task which remains to be done.

Mugabe’s focus on the African personality and the need to progress it, all over the world always came to the forefront. He followed the progress made by Africans everywhere in sport, the arts, film (even the Oscars were a focus), law and politics, science and technology, and in the diaspora, inclusive of African Americans who had a special place in his heart. His own intractable stand-off with Blair ignited by the land issue was in my humble submission never foisted for resolution on Barack Obama, the 44th President of the United States, who pledged to resolve the intractable problems of the world, such as Cuba.

This was a consequence of Mugabe’s carefully considered appreciation of the foreign policy and other intricacies and nuances which the first African-American President of the US had to navigate.

In a meeting with President Jacques Chirac of France in 1999, Mugabe was asked whether he thought that the then incoming President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, would measure up as president and be able to fill the shoes left by the great President Nelson Mandela. His response was: “Leaders build themselves up by their own actions”. Mugabe, a wise person who had a mind of his own, was loyal to his fellow African leaders; he never disparaged them to anyone.

Like him or not, Mugabe’s legacy cannot be erased from history. He was the author of many actions which could not be ignored. He was undoubtedly a leader of a struggle and a nation. Our founding father, he was a leader among leaders. In multi-lateral fora, he defined issues without fear or favour. He led and achieved results. He is our hero; Africa’s hero.

He had such a long life and did so many things and as a human being, he was like all of us humans, fallible. Indeed we all make mistakes. However, from the outpouring of grief I have noticed, especially from the common man and woman, including the criticisms from some people who suffered from him, many today appreciate the good he did and are genuinely mourning the man.

Some who were in the opposition during his rule have said that they recognise and appreciate his immense contribution to the birth and growth of Zimbabwe. His death can therefore serve to unite us all at various levels, as Zimbabweans. This would make us worthy successors to the good things he did.

As I mourn Mugabe, I regret that after 19 years of seeing him almost every day, circumstances did not allow me to say a proper goodbye. The last time I saw him was at his Blue Roof residence on November 21, 2017, when as Minister of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs I was tasked to go to Parliament, which was sitting at the Harare International Conference Centre that day, to deliver his resignation letter.

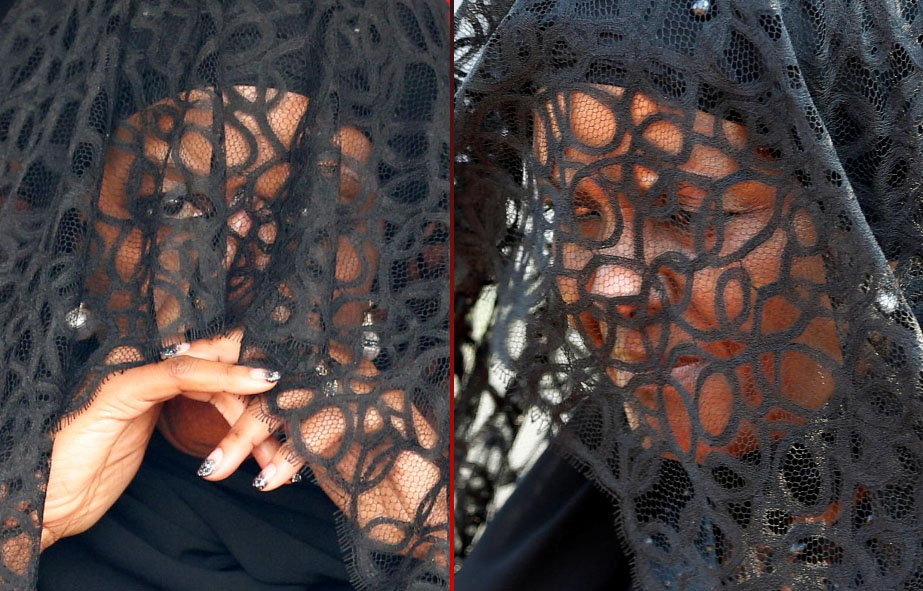

As I went out of that door at his Blue Roof house, I did not know that I would never again see someone who meant so much to me. To the Mugabe family, and especially Mrs Grace Mugabe, Bona and the boys – Robert (Junior) and Bellarmine – I extend the deepest and heartfelt condolences of my family and I.

I also lost my father and it is not easy, the pain never goes away. I urge you to find solace from the fact that he was a great man who had a long and illustrious life. He is being mourned by the majority of Zimbabweans, and many in Africa and around the world. For me personally, I say farewell Comrade President Robert Gabriel Mugabe, the leader of our revolution. I shall forever be grateful for your contribution to my liberation, education and intellectual development. You always appreciated me when I did well, and I promise that I will strive to put on a “good show” in all I do, and this in honour of your memory.

Go well Shefu, a leader among leaders, my icon, my hero, I will never forget. I will ever remember. Rest in Eternal Peace.

Bonyongwe is a former CIO Director-General and retired Major-General. This article was originally published by the Zimbabwe Independent