HARARE – The investor and I had just come to the realisation that the Victoria Falls Formula 1 Grand Prix project had been politically-infiltrated and most politicians wanted in at any cost. We decided to abandon buying the piece of land owned by the ministry of tourism and look for private land instead.

I had contacted the Mazoe Rural District Council. So it was not unusual to be called to their offices to discuss one or two possibilities.

It was in one such meeting that the CEO received a call. After the phone call, he slowly placed his phone on the desk. He wore an indecipherable expression. He looked at me and said: “Shami, John Bredenkamp wants to see you.”

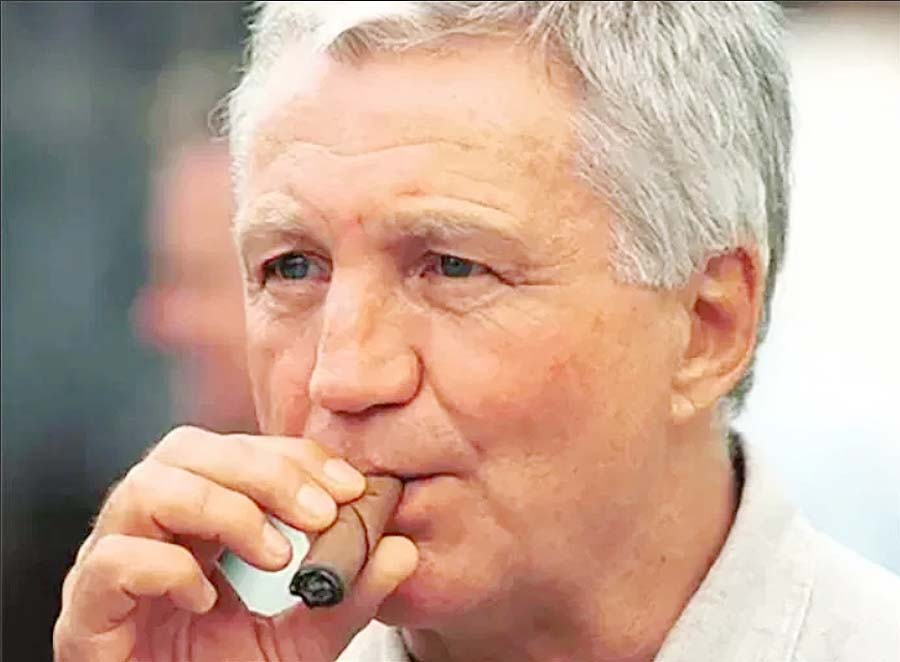

Now that was a bit of sailing arcana to me, and to the CEO so it seemed. I had heard of the gentleman. I knew he was one of Zimbabwe’s richest people, a billionaire according to some. I also knew he didn’t have a good reputation among Zimbabweans for he was known to be one of Robert Mugabe’s rich cronies.

I X-rayed my mind for any reason why this man would ask for a meet-up. My faculties were blank. The CEO was non-the-wiser. “Maybe he wants to sell his land for your Grand Prix. Afterall he has an aerodrome in Christon Bank,” he opined.

That sounded plausible and lessened my anxiety.

When does he want this meeting? I asked. “Now!”, came the answer. Shock is an understatement.

We drove to Harare soon after. I rode with my Chief Operations Officer, Albert Jimu. And the CEO drove separately. I had a feeling he was communicating with JB, as Bredenkamp was affectionately known, through a third party. To this day, I have no idea who the person was.

We arrived at JB’s 5th Avenue offices just before 2PM. I had never been there before. A quick glance at the building confirmed to me this wasn’t an ordinary place.

A guy in a black suit appeared from nowhere and just said “Shami?”. “Yes,” I nodded. “Park here,” was the directive. Only our two cars were parked in front of the building. Two or three men in black suits would walk back and forth along the 5th Avenue curb.

We sat there forever. The 3rd Party kept telling the CEO that JB was on his way. The type of cars entering the building were not ordinary cars we normally see on the streets of Harare. This wasn’t an ordinary man, I reminded myself.

Shortly after 3:45PM, two white Land Cruiser V8 vehicles came moving at tremendous speed and the gates were opened at once. The call came, we could go in.

The receptionist welcomed us with a choreographed smile and showed us where to sit. I looked at the CEO for clues but he preserved his usual austere mien. His observant eyes conveyed a preoccupation with a multitude thoughts, without giving a single one of them away.

Thirty minutes later, we were ushered into a massive room, carpeted wall-to-wall and a round table allowed for sitting.

Drinks were offered.

The room was unpeopled, with a few decorum paraphernalia and sedimentary deposits of a considerable antiquity.

“Hello, Shami is it?”, boomed a voice from the door.

A 6’ 4” or so gentleman of imposing and appealing girth approached me. I stood up and stretched my hand. “Mr Bredenkamp,” I retorted. He gestured for me to sit down. And he took a chair next to mine.

They exchanged greetings on first name basis with the CEO.

“Now, Shami, are you mad?!,” JB barked, without preamble. I could have fallen off my chair and spilt the coffee.

He continued regardless of my apparent confusion and shock.

“Look, I hear you’re trying to bring a Grand Prix to Zimbabwe? Girl, you are a dreamer. You are dreaming!”

He had this maniac look. There are times you bite your tongue and bide your time. I placed my cup of coffee back on the table.

I looked him dead in the eye, and said: “That’s true Mr Bredenkamp. What’s wrong with dreaming?”

He looked at me like I had committed a breach in etiquette by so addressing him. But frankly, I couldn’t care less because I felt attacked. The CEO looked at me, shocked. He was about to say something, but I lifted my palm in an ‘I’ve got this’ gesture, and he sat back uncomfortably.

Even JB didn’t expect I would respond that way. He held my hand and said, “Look, you are a nice lady and well-meaning. But you’re in the wrong country. You can’t do a Grand Prix in Africa.”

I hastened to remind him that South Africa used to have one in Durban during the apartheid era. And Zimbabwe used to host Moto GP competitions, even cycling.

He said “that’s right, but if you’re going to do it, do it in South Africa, not Zimbabwe.”

I asked him for the reasons, and also reminded him he still hadn’t explained to me why a Zimbabwean couldn’t or is not allowed to dream.

He looked at me for a moment. “Do you know I started the rugby club at Prince Edward single-handedly in Zimbabwe? I’ve done a lot for this country. I’ve 200 most powerful friends in the world. If we thought it was a good idea to bring the Grand Prix to Zimbabwe, you think we wouldn’t? Young lady, Zimbabwe is not going anywhere, mark my words.”

At this juncture, I wasn’t sure whether JB was a friend or foe. I said to him: “You and I are Zimbabweans I presume? So, if you know Zimbabwe isn’t going anywhere, what’s wrong with young people dreaming?”

“Do you know what is involved in the project?”

“Yes,” I replied.

He wanted to know the budget. I told him US$1.2 billion. The Tilke Group, the one that did 70 circuits the world over, were our architects and they had already an Environmental Impact Assessment. He asked some more questions. I cherry-picked which ones I answered fully, just in case I was talking to a foe or a competitor.

He pushed back his chair and stood up, paced about and then stood next to my chair.

Time to change tact.

“Do you know who sits up there?” he asked, gesturing to the 1st Floor. I genuinely had no idea. Without any invitation, he said: “Emmerson. Emmerson Mnangagwa and his sons.”

I was very surprised. “So, if you’re cohabiting with the First Family, why don’t you discuss with them the ills of Zimbabwe and where we are headed, in case your prophecy of an apocalypse in three months is true? As a concerned citizen, wouldn’t you want answers from your tenants?” I asked.

I was never ready for his reply. Yelling at the top of his lungs, he shouted: “HE’S CLUELESS!”

I was surprised. I thought of another question.

“You Sir, being a corporate giant in our country, what are you going to do?”

He screamed again: “I’M ALSO CLUELESS!”

He then softened and said to me, ‘Now Shami, can you just leave this Grand Prix project alone?” His expectant eyes almost pleading.

Whether the result of deduction, hope, intuition or merely stubbornness, I looked up and said: “Not for all the tea in China!”

He glowered at me, scandalised. I could tell the CEO was now enjoying the drama unfolding. He steadfastly maintained neutrality nonetheless.

JB then said to me. “Look, I can offer you the land and pay you US$20 million, if you want this project to go ahead.”

“I need that in writing,” I challenged him back.

He announced his office in Dubai had been following me to check on the progress and he had a full report on me. In less than no time, he was headed for the door.

The CEO was beside himself laughing. He said, “unopenga here Shami? Uyu mudhara-ka.” I wasn’t crazy, and I didn’t think I was being disrespectful.

“Larry, Larry, come here quick!” That was JB. Moments later, an impeccable gentleman stood by the doorway. Worry registered on his face, wondering what was going on.

Before we could exchange pleasantries, JB started: “Talk to her, Larry. She’s not listening to me. She wants to go ahead with that Grand Prix nonsense. Tell her, Larry.”

Larry seemed unmoved. But he nodded with the proprietary air of special knowledge.

I decided to bring Larry up to speed on our verbal agreement with JB earlier.

“Larry, shall I?” I was just checking if we were okay with first names. Permission was granted.

“Larry, I’m not willing to walk away from the US$20m challenge on the table right now. Although I’m yet to receive a written verbiage on the matter,” I said.

JB jumped in and said I hadn’t told him what I was willing to part with, in case my project failed.

I reminded JB that it was a mono-bet. I hadn’t gotten into a bet neither could I afford a bet. JB wanted US$1 million from me should I fail.

JB left the room without any excuse. Larry turned to me and said what his boss was trying to say in his impolite way was that the Grand Prix project, or any other big international project for that matter, could not be sustained in Zimbabwe due to a lot of variables. He politely asked me to be a bit patient.

This was in May 2019. He advised me to wait for the drama unfolding and the ever-changing currency policies to play out. He had a point. But something didn’t sit well with me. Why was the duo concerned? They didn’t know me from Adam.

I asked Larry where in Dubai was their office? He said they closed shop. I never divulged that his boss had said otherwise.

JB came back like the devil was chasing him. He looked demented to me. He started talking, ignoring whatever Larry was saying to me.

“Do you know they gazetted my farm?” That question was directed to me, and it caught me off-guard.

Who was “they,” I asked? JB gave me a look suggesting that I had missed something patently obvious.

“The government!” he barked.

Now I didn’t know what to say. Didn’t he say Emmerson Mnangagwa and Sons are his tenants? Why is he telling me this?

In an exaggerated pantomime of casualness, I asked why?

JB circumvented my question. Jabbing his thick finger on to the table, he announced the following: “I spent US$64 million building that farm. You should visit it and see how beautiful it is. It’s in Christon Bank. I’m 80-years-old now (he was 78). You (pointing at me) will never know any peace. (Counting his second finger), your kids will never know any peace and your grandchildren will never know any peace. Even if it means 10 years after I’m gone, I have 10 most powerful men in the world to make sure Zimbabwe suffers!”

Now jabbing his chest with such force which I estimated could have been three newtons per second, he told me to mark his words. I figured by “you”, he meant Zimbabweans.

Spoken by another person, this statement might have passed for rhetoric. As spoken by the gentleman in question, it was an unequivocal declaration of intent.

By now, I had reached the mortal limit of endurance. I asked JB a question that I had been itching to ask since he called for the meeting.

“Mr Bredenkamp, why am I here?”.

He went off on a tangent again, sometimes contradicting himself. To say the scene was confused would be like saying D-Day was hectic.

It was time for us to take our leave. He complimented my “intelligence”, “decorum”, “business acumen” and a Valentino bag that I was carrying that he pointed out to Larry, whistling, “Wheeeeew, a lady of class. Valentino!”

I pointed out that one of my sisters bought it for my mum and I helped myself to it.

They both saw us out. JB repeated that I make a plan to visit his farm for he needed my feedback. Larry and I were commanded to exchange numbers.

We made our exit, followed by voluble protestations of farewell, gratitude and good wishes. He waved me all the way to the car.

The CEO was to call me.

I drove off, with JB still waving. Never to see him again (I wasn’t to know). I did not visit the farm.

To this very day, I’m confused. Why me? Why did he call for the meeting? What did I miss? Why did he tell me about his farm? Why was I told not to dream?

As you now close your eyes permanently JB to rest in eternal peace, please give us a signal!

(John Bredenkamp died peacefully at his home in Harare on June 18, 2020, from kidney failure. He was 79)