HARARE – Zimbabwe on Thursday received 60,000kg (60 tonnes) in freshly-printed higher denomination bond notes, which the central bank says will go into circulation at the end of the month.

The RBZ announced last week that Z$10 and Z$20 bond notes were being printed to complement the Z$2 and $5 notes which have become valueless as the inflation-hit currency continues its side.

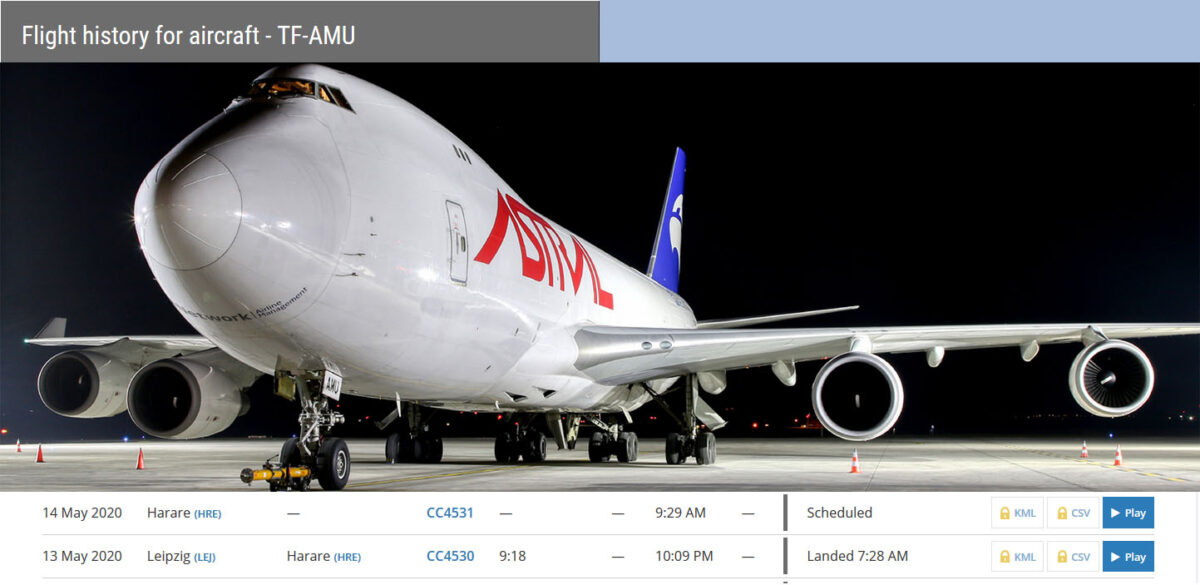

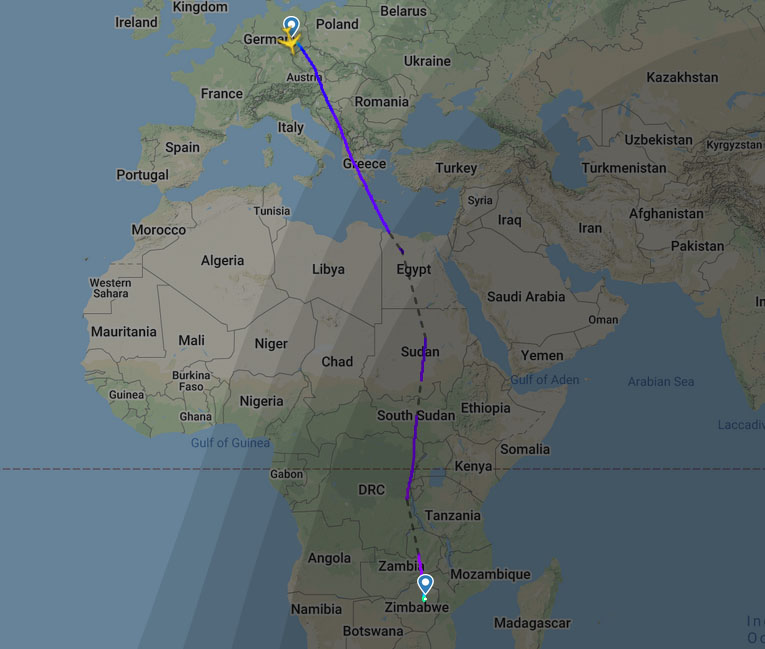

ZimLive has established that the new notes were delivered to Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport on Thursday morning by a Boeing 747-48EF(SCD) cargo plane which flew out of Leipzig in Germany.

The aircraft, registration TF-AMU, is owned by Air Atlanta Icelandic of Iceland.

A source told this website that the plane disgorged 60,000kg of bank notes.

The RBZ has previously refused to disclose where the bond notes are printed, while bond coins are known to be minted in South Africa.

Based on where the plane originated, it is highly likely the bank notes were printed by the Leipzig division of Giesecke & Devrient, a Munich-headquartered company which has a history of doing business with Rhodesia and its successor state Zimbabwe going back to 1965.

Giesecke & Devrient stopped printing Zimbabwean banknotes in 2008 after an “official request” from the German government. The company said in a statement at the time that its decision was “a reaction to the political tension in Zimbabwe, which is mounting significantly rather than easing as expected, and takes account of the critical evaluation by the international community, German government and general public.”

It would appear the company has re-opened its Zimbabwe account.

The state-run Sunday Mail newspaper reported last week that the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe has approved the introduction of Z$10 and Z$20 banknotes worth close to Z$600 million “to increase physical money supply and curb cash shortages.”

Currently, the RBZ says Z$1.4 billion in cash is circulating, and the higher denominated notes will increase this to about Z$2 billion.

Zimbabwe has Z$2 and Z$5 notes, and Z$1 and Z$2 coins, in circulation which make cash transactions cumbersome, with small transactions now requiring the carrying of huge wads of notes due to inflation which jumped to 676.39 percent year-on-year in March.

Cash shortages have triggered long queues at banks and a thriving illegal forex market where premiums of up to 40 percent are charged to convert money held in the bank into cash.

In addition, cash shortages have led to the creation of a multi-tier pricing system, where prices of a single product differ depending on the customer’s mode of payment.

Eddie Cross, a member of the RBZ’s Monetary Policy Committee, said banks will be required to exchange their electronic balances for physical cash to ensure that no new money is created.

“We’re moving cautiously because we don’t want to disturb the monetary balance and we’re insisting that banks pay for the currency when they draw it so that there’s no money creation,” Cross said.

“We’re now taking steps to start implementing that. We started in September last year when we had about Z$500 million worth of notes in circulation and now we have between Z$1.3 billion and Z$1.4 billion notes. This will take it up to Z$2 billion. Our target is Z$3 billion, which amounts to about 10 percent of our money supply.”

Zimbabwe is grappling with its worst economic crisis in a decade, marked by shortages of foreign exchange, medicines and cash as frustration over President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s government grows.

Zimbabwe reintroduced its currency, the Zimbabwe dollar, last June, ending a decade of dollarisation. But with no foreign or gold reserves to back it up, its value has plunged while inflation has soared as Zimbabweans fear a return to the 2008 hyperinflation period which forced the country to abandon the Zimbabwe dollar.

Finance minister Mthuli Ncube, in the letter to the International Monetary Fund dated April 2, warned that the country is headed for a health and economic “catastrophe” from the coronavirus pandemic because its debt arrears mean it cannot access foreign lenders.

Lenders like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank stopped lending to Zimbabwe in 1999 after the country defaulted on its debt repayments.

That has led the government to resort to domestic borrowing and money-printing to finance the budget deficit, pushing inflation to the second highest in the world.

Two weeks ago, Mnangagwa promised a US$720 million stimulus package for distressed companies, but did not say where the money would come from.

Ncube said cumulatively, Zimbabwe’s economy could contract by between 15 percent and 20 percent during 2019 and 2020, warning that this is a “massive contraction with very serious social consequences.”

Former finance minister Tendai Biti last week claimed Zimbabwe was so broke it was failing to pay its workers, and was creating fictitious money.

“The regime is broke and broke in absolute terms. The coffers are empty and they are generating salaries through the RTGS ponzi scheme. To date, Treasury has not disbursed social protection payments to the ministry of social services. Tobacco sales have had a poor start and donors are not coming on board,” the MDC Alliance deputy president said.