LONDON, United Kingdom – Zimbabwe’s new sovereign wealth fund reportedly paid $1.6 billion — 5 percent of GDP — for shares in a mining conglomerate with recent links to Kudakwashe Tagwirei, a presidential advisor and ruling party donor accused of corruption.

Sources confirm that the county’s debt has leapt by $3 billion—from $18 billion to $21 billion—in just a few months, as Treasury Bills worth almost 10 percent of GDP have been issued since November 2023.

Of that new debt, $1.9 billion is to “recapitalise” the Mutapa Investment Fund, Zimbabwe’s new sovereign wealth fund, while $900 million has been allocated to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe.

Mutapa, named after an ancient kingdom, has taken over the shares of more than 20 state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The jewel in Mutapa’s crown is Kuvimba Mining House, which owns around a dozen gold, lithium, nickel, and platinum mines.

Until recently, the state-owned 65 percent of Kuvimba, and private investors held 35 percent of the shares. In April 2024, however, it was reported that Mutapa bought out the private investors for $1.6 billion using a Treasury Bill — a form of short-term government debt akin to an IOU (document acknowledging a debt).

If this figure is accurate, then about four fifths of the $1.9 billion debt incurred to allow Mutapa to revive failing SOEs has been used to pay a few private individuals. A $1.6 billion price tag for a 35 percent stake would value Kuvimba at $4.6 billion overall — triple the $1.5 billion valuation given to Kuvimba by the government in 2022. This would raise serious questions about whether Mutapa has grossly overvalued the shares.

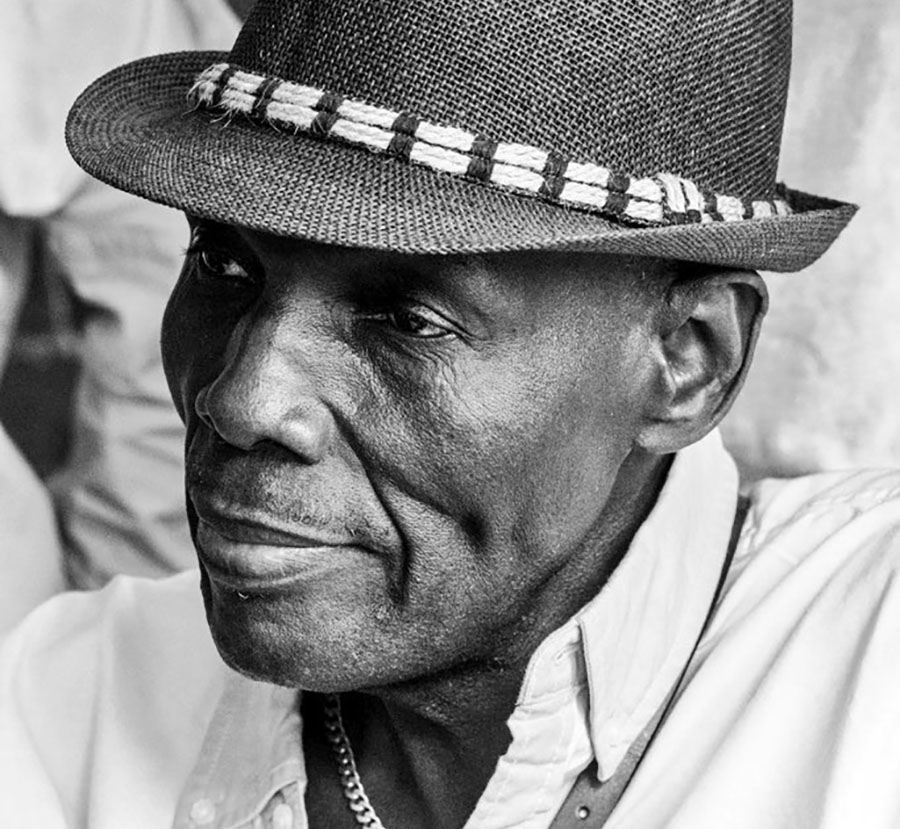

Who Got Paid?

In 2021, The Sentry revealed that Kuvimba’s private investors included Pfimbi Resources, a company controlled by Tagwirei. Pfimbi was a shareholder of Ziwa Resources, which in turn held shares in Kuvimba. This analysis was later updated to show that Pfimbi — a Shona word that carries connotations of “secret stash” — was owned by two trusts: the Kudakwashe Tagwirei Trust, whose beneficiaries were his family, and the Eagles Trust, whose beneficiaries were unknown.

Pfimbi’s corporate documents list a lawyer regularly used by Tagwirei as the point of contact for both trusts. Tagwirei denies any link to Kuvimba, but well-informed sources say that he was making key decisions at the firm as late as September 2023, just before Mutapa’s purchase of the Kuvimba shares.

Mutapa frames the $1.6 billion buyout as an opportunity to end speculation about Kuvimba’s ownership. A cheaper way to lay the matter to rest would have been to publish the records for Kuvimba, Ziwa, and the Eagles Trust, which are missing from official registries. Given their absence — itself a red flag, considering that other companies with missing records include politically sensitive firms such as the president’s farm and military entities — it is impossible to be certain who the ultimate beneficiaries of the Mutapa payment were.

Did Mutapa Overpay?

If the report that Mutapa paid $1.6 billion for 35 percent of Kuvimba is accurate, then the whole firm would be valued at $4.6 billion. This is three times the government’s previous $1.5 billion valuation in 2022 and much more than the amount — likely to be in the low hundreds of millions of dollars — that Tagwirei’s firms spent in 2019 when acquiring the mines, before they transferred the assets to Kuvimba in 2020.

Soaring gold prices since 2020 might explain some of the increase in value: The group’s present gold production might bring in about $250 million a year, before costs and taxes. However, a $4.6 billion valuation seems distinctly frothy given that Kuvimba’s other mines have had mixed fortunes: Declining lithium prices have caused stockpiling, and the firm’s platinum and nickel projects are either inactive or loss making.

Public Debt, Private Wealth?

Zimbabwe is currently in debt distress, unable to access cheap loans from development banks because of past defaults and substantial arrears. The African Development Bank (AfDB) is attempting to herd Zimbabwe and its creditors towards a debt restructuring process.

Achieving sustainable levels of borrowing that can be serviced by domestic taxes requires bilateral government and commercial creditors to reduce the amounts owed to them — this is known as “taking a haircut.” More borrowing makes debt sustainability agreements harder to reach because it increases the sacrifice required by existing creditors.

Clarity over Zimbabwe’s level of debt — and whom it is owed to — is important to keep the AfDB debt restructuring process going, and creditors have been asking pointed questions after hearing conflicting accounts about how much Zimbabwe owes. Lenders may not be comforted that debt has leapt to $21 billion and that new debt amounting to 5 percent of GDP appears to have been issued for the purpose of paying shareholders in Kuvimba with possible links to a crony businessman.

The point of sovereign wealth funds is to preserve and grow wealth to benefit Zimbabwean citizens. If the report of $1.6 billion paid to Kuvimba’s private investors is true, Zimbabwean taxpayers — who will have to repay this debt — should be angry that one of the first acts of their new sovereign wealth fund may have been to allocate wealth from the many to the few.

Recommendations

Zimbabwe’s independent Auditor General has the remit to audit public expenditure, including by state-owned entities such as the Mutapa Investment Fund. Auditor General reports frequently trigger hearings by the parliamentary Public Accounts Committee (PAC). Both the Auditor General and the PAC should urgently open inquiries into Mutapa’s acquisition of shares in Kuvimba. The PAC hearings should be held in public.

These five questions should underpin any inquiry:

► What was the purchase price?

► How was the valuation carried out?

► What was the full ownership structure of Kuvimba at the time of payment?

► Who got paid?

► What happened to the Treasury Bill after it was issued?

If any wrongdoing is found, the Auditor General and the PAC should refer the matter to the police and the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission.

Banks and Commercial Counterparties

Banks and other financial institutions should conduct enhanced due diligence into any entity seeking to sell (“discount”) the Treasury Bill described in this report. In the past, when Sakunda, a Tagwirei-controlled company, was given a $366 million Treasury Bill for its role in running an agricultural programme, it sold parts of the debt instrument to banks at a discount in order to get access to hard currency.

The banks would then hold that Treasury Bill until it matured, when they could go to the central bank and redeem it for its face value plus interest.

Multilateral Development Banks

Issues raised by the new debt issuance should be discussed in the AfDB-led structured dialogues on debt clearance, including those working groups that include civil society representatives, so that the government of Zimbabwe can explain the thinking behind the purchase of the Kuvimba shares.

The AfDB should push the government of Zimbabwe to publish a list of the entities and financial institutions holding the domestic debt, including this particular Treasury Bill. – The Sentry